更新

2021年5月23日: 現在有 印尼語 翻譯可用,感謝 Ariandy/1kb。

2021年4月2日: 增加 BuyMeACoffee 連結 給那些想請我喝杯咖啡的人。

2021年2月1日: Youtube影片! 兩個月後: 到2021年4月1日為止,總共有186支影片全部完成(稍微超過23小時)。

2021年1月4日: mdBook 線上閱讀。

2020年11月28日: 現在也有簡體中文 翻譯可用,感謝 kumakichi!

2021年11月27日: 現在有韓語錄製的Easy Rust影片了! 한국어판 비디오도 녹화 시작!

介紹

Rust 是一門已經有了很好教科書的新程式設計語言。但有時候它的教材很難,因為難在它是寫給以英語為母語的人看的。現在有許多公司及人們在學習 Rust,如果能有一本使用簡單英語寫的書,他們可以學習得更快。這本書就是用簡單英語寫給這些公司和人們來學習 Rust 的。

Rust 是一門相當新卻已經非常流行的程式設計語言。它之所以受歡迎,是因為它給了你 C 或 C++ 的運作速度和控制能力,但也有在其他像 Python 等較新型語言上有的記憶體安全機制。它有時以不同於其他語言的新想法做到這一點。這也意味著需要學習一些新東西,不能只是"邊走邊想辦法"。Rust 更是一門你必須思考一段時間才能理解的語言。但它看起來還是蠻熟悉的如果你會其他程式設計語言的話,它是為了幫助你寫好程式碼而生的。

我是誰?

我是一個生活在韓國的加拿大人,我在寫 Easy Rust 的同時,也在思考如何讓這裡的公司更容易開始使用它。我希望其他母語不是英語的國家也能使用它。

簡單英語學 Rust

簡單英語學Rust 寫於 2020 年 7 月至 8 月,長達400多頁。如果你有任何問題,可以在這裡或在 LinkedIn 上或在 Twitter 上聯絡我。如果你發現有什麼不對的地方,或者要提出 pull request,去做吧。已經有超過 20 人幫助我們修復了程式碼中的錯別字和問題,所以你也可以。我不是世界上最好的 Rust 專家,所以我總是喜歡聽到新的想法,或者看看哪裡可以讓這本書變得更好。

- 第一部 - 瀏覽器中的 Rust

- Rust Playground

- 🚧 和 ⚠️

- 註解

- 型別

- 型別推導

- 列印 hello, world!

- 顯示和除錯

- 可變性

- 堆疊、堆積和指標

- 更多關於列印

- 字串

- const 和 static

- 更多關於參考

- 可變參考

- 傳遞參考給函式

- 複製型別

- 集合型別

- 向量

- 元組

- 控制流程

- 結構體

- 列舉

- 迴圈

- 實作結構體和列舉

- 解構

- 參考和點運算子

- 泛型

- Option 和 Result

- 其他集合型別

- 問號(?)運算子

- 特徵

- 鏈結方法

- 疊代器

- 閉包

- dbg! 巨集和 .inspect

- &str 的種類

- 生命週期

- 內部可變性

- Cow

- 類型別名

- todo! 巨集

- Rc

- 多執行緒

- 函式中的閉包

- impl 特徵

- Arc

- 通道

- 閱讀 Rust 文件

- 屬性

- Box

- Box 包裹的特徵

- Default 和生成器模式

- Deref 和 DerefMut

- Crates 和模組

- 測試

- 外部 crates

- 標準函式庫之旅

- 撰寫巨集

- 第二部 - 電腦上的 Rust

第一部 - 瀏覽器中的 Rust

本書有分兩部。第一部,你將在瀏覽器中就能學到儘可能多的 Rust 知識。實際上你幾乎可以在不安裝 Rust 的情況下學到所有你需要知道的東西,所以第一部非常長。最後是第二部。它要短得多,是關於電腦上的 Rust。在這裡,你將學習到其他一切你需要知道的、只能在瀏覽器之外進行的事情。例如:處理檔案、接受使用者輸入、圖形和個人設定。希望在第一部結束時,你會喜歡 Rust 到想安裝它。如果你不喜歡,也沒問題──第一部教了你很多,你不會介意的。

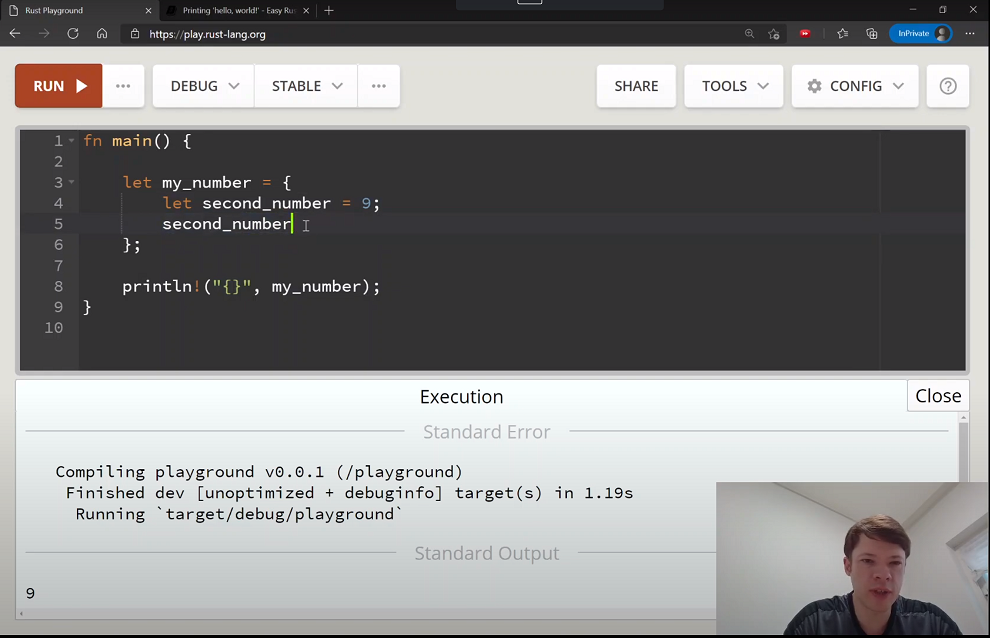

Rust Playground

也許你還不想安裝 Rust,這也沒關係。不用離開瀏覽器你可以去https://play.rust-lang.org/,開始寫 Rust。你可以在那裡寫下你的程式碼,然後點選 Run 來檢視結果。你可以在瀏覽器裡用 Playground 裡面執行本書中大多數的範例。只有在接近本書結尾的時候,才會看到無法在 Playground 操作的範例(比如開啟檔案)。

以下是使用 Rust Playground 時的一些提示。

- 用 RUN 來執行你的程式碼

- 如果你想讓你的程式碼更快,就把 DEBUG 改為 RELEASE 模式。 Debug:編譯速度較快,執行速度較慢,包含除錯資訊。Release:編譯速度較慢,執行速度較快,移除除錯資訊。

- 點選 SHARE ,得到當下程式碼的網址連結。如果你需要幫助,可以用它來分享你的程式碼。點選 SHARE 後,你可以點選

Open a new thread in the Rust user forum,馬上向論壇那裡的人尋求幫助。 - TOOLS: Rustfmt 會幫你的程式碼排版好。

- TOOLS: Clippy 會給你如何讓程式碼更好的額外資訊。

- CONFIG: 你可以在這裡把你的主題改成黑暗模式,方便在晚上工作,以及很多其他配置。

如果你想安裝 Rust,請到官方網站安裝頁面,然後按照說明操作。通常你會使用 rustup 來安裝和更新 Rust。

🚧 和 ⚠️

有時書中的程式碼範例是不能用的。如果一個範例不能用,它將會有一個 🚧 (施工路障 emoji)或 ⚠️ (警告標誌 emoji)在裡面。🚧 就像"正在建設中"一樣:它意味著程式碼不完整。Rust 需要一個 fn main()(一個主函式)來執行,但有時我們只是想看一些小的程式碼,所以它不會有 fn main()。這些範例是正確的,但需要一個 fn main() 讓你執行。而有些程式碼範例是向你展示一個我們將解決的問題。那些可能有一個 fn main(),但會產生錯誤,所以它們會有一個⚠️。

註解

註解是給程式設計師看的,而不是給電腦看的。寫註解是為了幫助別人理解你的程式碼。這也有利於幫助你以後理解你的程式碼。 (很多人寫了很好的程式碼,但後來卻忘記了他們為什麼要寫它。)在 Rust 中寫註解,你通常會使用 //:

fn main() { // Rust 程式從 fn main() 開始 // 程式碼放在區塊中,用 { 開始和 } 結束 let some_number = 100; // 我們寫多少在這裡都可以,編譯器都不會看 }

當你這樣做時,編譯器不會看到出現在 // 右邊的任何東西。

還有一種註解是,你可以用 /* 開頭,以 */ 結尾。這種寫法在程式碼中間很有用。

fn main() { let some_number/*: i16*/ = 100; }

對編譯器來說,let some_number/*: i16*/ = 100; 看起來就跟 let some_number = 100; 一樣。

/* */ 註解形式對於超過一行的非常長的註釋也很有用。在這個範例中,你可以看到你需要為每一行去寫 //。但是如果你輸入 /*,它不會停止註解,直到你用 */ 結束這個註解。

fn main() { let some_number = 100; /* 讓我來告訴你 有關這個數字的一些事情。 它是100,我最愛的數字。 他叫做 some_number 但實際上我思考的是… */ let some_number = 100; // 讓我來告訴你 // 有關這個數字的一些事情。 // 它是100,我最愛的數字。 // 他叫做 some_number 但實際上我思考的是… }

型別

Rust 有許多型別,讓你可以處理數字、字元等等。有些型別很簡單,有些型別比較複雜,你甚至可以建立自己的型別。

原始型別

Rust 有簡單的型別,這些型別被稱為原始型別(原始 = 非常基本)。我們將從整數和 char(字元)開始。沒有包含小數點的一整個數字就是整數。整數有兩種型別:

- 有符號整數

- 無符號整數

符號是指 + (加號)與 - (減號),所以有符號整數可以是正數,也可以是負數(如 +8,-8)。但無符號整數只能是正數,因為它們沒有符號。

有符號整數是 i8、i16、i32、i64、i128 和 isize。

無符號整數是 u8、u16、u32、u64、u128 和 usize。

i 或 u 後面的數字表示該數字的位元數,所以位元數愈多的可以表示更大的數字。8 位元 = 一個位元組,所以 i8 是佔用一個位元組空間的型別,i64 是 8 個位元組,以此類推。尺寸較大的數字型別可以容納更大的數字。例如,u8 最多可以容納最大的數字是 255,但 u16 最多可以容納 65535。而 u128 最多可以容納 340282366920938463463374607431768211455。

那什麼是 isize 和 usize 呢?這表示你的電腦類型的位元數。(你的電腦裡中央處理器的位元數叫做電腦的架構)。所以在 32 位元電腦上的 isize 和 usize 就像是 i32 和 u32,64 位元電腦上的 isize 和 usize 就像是 i64 和 u64。

需要不同整數型別的原因有很多。其中之一是電腦效能:位元組數量愈少處理速度愈快。例如,數字 -10 在 i8 是 11110110,但在 i128 會是11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111110110。不過這裡它還有一些其它用途:

Rust 中的字元稱做 char。每一個 char 都對應到一個數字:字母 A 對應到數字 65,而字元 友 (中文的"朋友")對應數字 21451。這個數字列表被稱為 "Unicode"。Unicode 給愈常用的字元使用愈小的數字,如字母 A 到 Z,數字 0 到 9,或空格等等。

fn main() { let first_letter = 'A'; let space = ' '; // ' ' 裡的空白也算一個字元 let other_language_char = 'Ꮔ'; // 感謝 Unicode,其它語言像是切羅基語 (Cherokee) 也顯示的很好 let cat_face = '😺'; // Emojis 也算字元 }

最常用字元的對應數字少於 256,剛好可以放進 u8 裡。要記得,u8 是 0 加上到 255 的所有數字,總共 256 種。這意味著 Rust 能使用 as 關鍵字安全地將一個 u8 轉換型別(cast) 為 char。("轉換 u8 為 char" 意味著 "假裝 u8 是char")

透過 as 轉型很有用,因為 Rust 對型別非常嚴格。它總是必需知道是什麼型別,也不會讓你一起用不同的兩種型別,即使它們都是整數。舉例來說,不能這樣用:

fn main() { // main() 是 Rust 程式開始執行的地方。程式碼會放在 {} (大括號)裡 let my_number = 100; // 我們沒有寫出整數的型別, // 因此 Rust 選擇了 i32。 // Rust 總是給整數選擇 i32, // 如果你不教它用不同型別的話。 println!("{}", my_number as char); // ⚠️ }

編譯器給的理由是:

error[E0604]: only `u8` can be cast as `char`, not `i32`

--> src\main.rs:3:20

|

3 | println!("{}", my_number as char);

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

幸運的是,我們可以用 as 輕鬆修正這個錯誤。我們無法將 i32 轉型為 char,但我們可以將 i32 轉型為 u8。接著我們同樣可以將 u8 轉型為 char。所以在同一行中,我們先用 as 讓 my_number 變成 u8,再變成 char。現在它就能通過編譯了:

fn main() { let my_number = 100; println!("{}", my_number as u8 as char); }

它會印出 d 是因為它就是100對應的 char。

然而,更簡單的方法是你只要告訴 Rust 說 my_number 的型別是 u8。你要像這樣做:

fn main() { let my_number: u8 = 100; // 更改 my_number 為 my_number: u8 println!("{}", my_number as char); }

所以這些是 Rust 中會有不同整數型別的兩個原因。這裡還有一個原因:usize 是 Rust 用來 索引 的型別。(索引的意思是"哪項是第一","哪項是第二"等等) usize 是最佳的索引型別,因為:

- 索引值不能是負數,所以它需要是一個帶 u 的數字(註:指無符號數)

- 它要可以夠大,因為有時你需要索引很多東西,但是

- 它不能是

u64,因為 32 位元電腦無法使用u64。

所以Rust使用了 usize,這樣你的電腦就能以它能讀取到的最大整數值進行索引。

我們再來了解一下 char。你會看到 char 總是一個字元,並且使用 '' 而不是 ""。

所有的 chars 都使用 4 個位元組的記憶體,因為 4 個位元組足以容納任何種類的字元:

- 基本字母和符號通常只需要 4 個位元組中的1個:

a b 1 2 + - = $ @ - 其他字母,如德文元音變音 (Umlauts) 或重音,需要 4 個位元組中的 2 個:

ä ö ü ß è é à ñ - 韓文、日文或中文字元需要 3 或 4 個位元組:

國 안 녕

當使用字元作為字串的一部分時,字串是用每個字元所需的最少記憶體來編碼的。

我們可以自己用 .len() 來觀察這個情況。

fn main() { println!("Size of a char: {}", std::mem::size_of::<char>()); // 4 位元組 println!("Size of string containing 'a': {}", "a".len()); // .len() 給出以位元組為單位的字串大小 println!("Size of string containing 'ß': {}", "ß".len()); println!("Size of string containing '国': {}", "国".len()); println!("Size of string containing '𓅱': {}", "𓅱".len()); }

這個程式會印出:

Size of a char: 4

Size of string containing 'a': 1

Size of string containing 'ß': 2

Size of string containing '国': 3

Size of string containing '𓅱': 4

你可以看到 a 的大小是一個位元組,德文的 ß 是兩個位元組,日文的 國 是三個位元組,古埃及的 𓅱 是四個位元組。

fn main() { let slice = "Hello!"; println!("Slice is {} bytes.", slice.len()); let slice2 = "안녕!"; // 韓文的 "hi" println!("Slice2 is {} bytes.", slice2.len()); }

這個程式會印出:

Slice is 6 bytes.

Slice2 is 7 bytes.

slice 長 6 個字元,佔 6 個位元組,但 slice2 長 3 個字元,佔 7 個位元組。

如果 .len() 給出的是以位元組為單位的大小,那麼以字元為單位的大小呢?我們在後面會學習這些方法,但這裡你只要記得 .chars().count() 做得到這件事就可以了。.chars().count() 會將你寫的東西變成字元,然後算出有多少個。

fn main() { let slice = "Hello!"; println!("Slice is {} bytes and also {} characters.", slice.len(), slice.chars().count()); let slice2 = "안녕!"; println!("Slice2 is {} bytes but only {} characters.", slice2.len(), slice2.chars().count()); }

這個程式會印出:

Slice is 6 bytes and also 6 characters.

Slice2 is 7 bytes but only 3 characters.

型別推導

型別推導的意思是,如果你沒有告訴編譯器型別,但它可以自己判斷時它就會自己決定型別。編譯器總是必需知道變數的型別,但你不需要都告訴它。實際上,通常你不需要告訴它。例如,像 let my_number = 8,my_number 將會是 i32。這是因為如果你不告訴它,編譯器會給整數選擇 i32。但是如果你說 let my_number: u8 = 8,它就會把 my_number 視為 u8,因為你明確告訴它是 u8。

通常編譯器都能猜到。但有時你需要告訴它,原因有兩個:

- 你正在做一些非常複雜的事情,而編譯器不知道你想要的型別。

- 你想要一個不同的型別 (例如,你想要一個

i128,而不是i32)。

這時可以指定一個型別,只要在變數名後新增一個冒號和型別。

fn main() { let small_number: u8 = 10; }

對數字來說,你可以在數字後面加上型別。你不需要空格──只需要在數字後面直接輸入。

fn main() { let small_number = 10u8; // 10u8 = 型別為 u8 的 10 }

如果你想讓數字容易閱讀,也可以加上 _。

fn main() { let small_number = 10_u8; // 好讀 let big_number = 100_000_000_i32; // 用 _ 時更容易讀出是 100 百萬 }

_不會改變數字。它只是為了讓你方便閱讀。而且你用多少個_都沒有關係。

fn main() { let number = 0________u8; let number2 = 1___6______2____4______i32; println!("{}, {}", number, number2); }

這個程式會印出 0, 1624.

浮點數

浮點數是帶有小數點的數字。5.5 是一個浮點數,6 是一個整數。5.0 也是一個浮點數,甚至 5. 也是一個浮點數。

fn main() { let my_float = 5.; // Rust 看到 . 時,知道它是 float }

但寫出型別時不叫 float,叫 f32 和 f64。這點和整數一樣:f 後面的數字顯示的是位元數。如果你不寫型別,Rust 會選擇 f64。

當然,只有同樣型別的浮點數可以一起使用。所以你不能把 f32 和 f64 加起來。

fn main() { let my_float: f64 = 5.0; // 這是 f64 let my_other_float: f32 = 8.5; // 這是 f32 let third_float = my_float + my_other_float; // ⚠️ }

當你嘗試執行這個程式時,Rust 會說:

error[E0308]: mismatched types

--> src\main.rs:5:34

|

5 | let third_float = my_float + my_other_float;

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ expected `f64`, found `f32`

當你用錯型別時,編譯器會寫 "expected (type), found (type)"。它是像這樣讀你的程式碼:

fn main() { let my_float: f64 = 5.0; // 編譯器見到 f64 let my_other_float: f32 = 8.5; // 編譯器見到 f32 是個不同型別 let third_float = my_float + // 你想把 my_float 加上什麼,所以它一定要是 f64 加上另一個 f64。現在它預期有另一個 f64… let third_float = my_float + my_other_float; // ⚠️ 不過它發現是個 f32。它沒辨法把它們加起來。 }

所以當你看到 "expected(type), found(type)" 時,你必須找到為什麼編譯器預期的是不同的型別。

當然,單純的數字很容易修正。你可以用 as 把 f32 轉型成 f64:

fn main() { let my_float: f64 = 5.0; let my_other_float: f32 = 8.5; let third_float = my_float + my_other_float as f64; // my_other_float as f64 = 把 my_other_float 當 f64 來用 }

或者更簡單,去掉型別宣告。("宣告一個型別" = "告訴Rust使用該型別") Rust會選擇可以加在一起的型別。

fn main() { let my_float = 5.0; // Rust 會選 f64 let my_other_float = 8.5; // 這裡還是會選 f64 let third_float = my_float + my_other_float; }

Rust 編譯器很聰明,如果你需要 f32,就不會選擇 f64:

fn main() { let my_float: f32 = 5.0; let my_other_float = 8.5; // 通常 Rust 是選 f64, let third_float = my_float + my_other_float; // 但現在它知道你需要把它加上 f32。所以它也選了 f32 給 my_other_float }

列印 hello, world!

當你啟動一個新的Rust程式時,它總是有這樣的程式碼。

fn main() { println!("Hello, world!"); }

fn的意思是函式,main是啟動程式的函式。()表示我們沒有給函式任何變數來啟動。

{} 被稱為程式碼區塊。這是程式碼所在的空間。

println! 是一個列印訊息到控制台(console)的巨集,。一個巨集就像一個為你寫程式碼的函式。巨集名稱後面都有一個 !。我們以後會學習如何建立巨集。現在只要記住有 ! 表示它是一個巨集。

為了學習 ;,我們將建立另一個函式。首先,在 main 中,我們將印出數字 8。

fn main() { println!("Hello, world number {}!", 8); }

println! 中的 {} 的意思是 "把變數放在這裡面"。這樣就會印出 Hello, world number 8!。

我們可以像之前一樣,放更多的東西進去。

fn main() { println!("Hello, worlds number {} and {}!", 8, 9); }

這將會印出 Hello, worlds number 8 and 9!。

現在我們來建立函式。

fn number() -> i32 { 8 } fn main() { println!("Hello, world number {}!", number()); }

這個程式也會印出 Hello, world number 8!。當 Rust 觀察到 number() 時,它看到一個函式。這個函式:

- 沒有用到引數(因為它是

()) - 回傳一個

i32。->(稱為 "瘦箭")右邊顯示了函式回傳內容的型別

函式內部只有 8。因為行尾沒有 ;,所以這就是它回傳的值。如果它有 ;,它將不會回傳任何東西(意思是它會回傳 ())。如果它有 ;,Rust 將無法編譯,因為回傳的是 i32,而 ; 回傳 (),不是 i32:

fn main() { println!("Hello, world number {}", number()); } fn number() -> i32 { 8; // ⚠️ }

5 | fn number() -> i32 {

| ------ ^^^ expected `i32`, found `()`

| |

| implicitly returns `()` as its body has no tail or `return` expression

6 | 8;

| - help: consider removing this semicolon

這意味著 "你告訴我 number() 回傳的是 i32,但你加了 ;,它就沒回傳值了"。所以編譯器建議去掉分號。

你也可以寫 return 8;,但在Rust中,正常情況下只需將;去掉即可回傳。

當你想提供變數給函式時,把它們放在 () 裡。還必須給它們命名並寫上型別。

fn multiply(number_one: i32, number_two: i32) { // 兩個 i32 傳入函式。將它們取名為number_one和number_two。 let result = number_one * number_two; println!("{} times {} is {}", number_one, number_two, result); } fn main() { multiply(8, 9); // 可以直接給數值 let some_number = 10; // 或者宣告兩個變數 let some_other_number = 2; multiply(some_number, some_other_number); // 把它們給函式當作引數 }

我們也可以回傳 i32。只要把行尾的分號拿掉就可以了:

fn multiply(number_one: i32, number_two: i32) -> i32 { let result = number_one * number_two; println!("{} times {} is {}", number_one, number_two, result); result // 這是我們要回傳的 i32 } fn main() { let multiply_result = multiply(8, 9); // 我們用multiply()印出結果並回傳給multiply_result }

宣告變數和程式碼區塊

使用 let 宣告變數(宣告一個變數 = 告訴 Rust 建立一個變數)。

fn main() { let my_number = 8; println!("Hello, number {}", my_number); }

變數使用範圍的開始和結束都在程式碼區塊 {} 內。在這個例子中,my_number 在我們呼叫 println! 之前結束,因為它在自己的程式區碼塊裡面。

fn main() { { let my_number = 8; // my_number 在這裡開始 // my_number 在這裡結束! } println!("Hello, number {}", my_number); // ⚠️ 沒有 my_number,而且 // println!() 也找不到它 }

你可以用程式碼區塊來回傳一個值:

fn main() { let my_number = { let second_number = 8; second_number + 9 // 沒分號,程式碼區塊回傳 returns 8 + 9。 // 就像函式一樣運作 }; println!("My number is: {}", my_number); }

如果在程式碼區塊內結束前加上分號,它將回傳 () (沒有值):

fn main() { let my_number = { let second_number = 8; // 宣告 second_number, second_number + 9; // 加 9 到 second_number // 但沒回傳它! // second_number 現在就結束 }; println!("My number is: {:?}", my_number); // my_number 會是 () }

那麼為什麼我們要寫 {:?} 而不是 {} 呢?我們現在就來談談這個問題。

顯示和除錯

Rust 中單純的變數可以在 println! 裡用 {}1 來被印出。但是有些變數不能,你需要用 除錯列印(debug print)。除錯列印是給程式設計師用的列印方法,因為它通常會顯示更多的資訊。除錯(Debug)有時看起來並不漂亮,因為它有額外的資訊來幫助你。

你怎麼知道你是否需要 {:?}2 而不是 {}?編譯器會告訴你。比如說:

fn main() { let doesnt_print = (); println!("This will not print: {}", doesnt_print); // ⚠️ }

當我們執行這個程式時,編譯器會說:

error[E0277]: `()` doesn't implement `std::fmt::Display`

--> src\main.rs:3:41

|

3 | println!("This will not print: {}", doesnt_print);

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^ `()` cannot be formatted with the default formatter

|

= help: the trait `std::fmt::Display` is not implemented for `()`

= note: in format strings you may be able to use `{:?}` (or {:#?} for pretty-print) instead

= note: required by `std::fmt::Display::fmt`

= note: this error originates in a macro (in Nightly builds, run with -Z macro-backtrace for more info)

這有相當多的資訊,但重要的部分是 you may be able to use {:?} (or {:#?} for pretty-print) instead。這意味著你可以試試 {:?},也可以試試 {:#?}。{:#?} 叫做"漂亮列印"。它和 {:?} 一樣,但是用更多行和不同的格式印出內容。所以 Display 意思是用 {} 列印,Debug 則是用 {:?} 列印。還有一點:如果你不想要換行,你也可以使用 print! 而不需要有 ln。

fn main() { print!("This will not print a new line"); println!(" so this will be on the same line"); }

這個將會印出 This will not print a new line so this will be on the same line。

譯註: 即顯示列印 (Display print)。

譯註: 除錯列印的格式。

最小和最大的數

如果你想知道最小和最大的數字,你可以在型別名稱後使用 MIN 和 MAX:

fn main() { println!("The smallest i8 is {} and the biggest i8 is {}.", i8::MIN, i8::MAX); // 提示: 印出 std::i8::MIN 表示 "列印在標準函式庫裡 i8 型別的 MIN 值" println!("The smallest u8 is {} and the biggest u8 is {}.", u8::MIN, u8::MAX); println!("The smallest i16 is {} and the biggest i16 is {}.", i16::MIN, i16::MAX); println!("The smallest u16 is {} and the biggest u16 is {}.", u16::MIN, u16::MAX); println!("The smallest i32 is {} and the biggest i32 is {}.", i32::MIN, i32::MAX); println!("The smallest u32 is {} and the biggest u32 is {}.", u32::MIN, u32::MAX); println!("The smallest i64 is {} and the biggest i64 is {}.", i64::MIN, i64::MAX); println!("The smallest u64 is {} and the biggest u64 is {}.", u64::MIN, u64::MAX); println!("The smallest i128 is {} and the biggest i128 is {}.", i128::MIN, i128::MAX); println!("The smallest u128 is {} and the biggest u128 is {}.", u128::MIN, u128::MAX); }

將會印出:

The smallest i8 is -128 and the biggest i8 is 127.

The smallest u8 is 0 and the biggest u8 is 255.

The smallest i16 is -32768 and the biggest i16 is 32767.

The smallest u16 is 0 and the biggest u16 is 65535.

The smallest i32 is -2147483648 and the biggest i32 is 2147483647.

The smallest u32 is 0 and the biggest u32 is 4294967295.

The smallest i64 is -9223372036854775808 and the biggest i64 is 9223372036854775807.

The smallest u64 is 0 and the biggest u64 is 18446744073709551615.

The smallest i128 is -170141183460469231731687303715884105728 and the biggest i128 is 170141183460469231731687303715884105727.

The smallest u128 is 0 and the biggest u128 is 340282366920938463463374607431768211455.

可變性

當你用 let 宣告變數時,它是不可變的(immutable,內容不可被變動)。

這個程式不能編譯:

fn main() { let my_number = 8; my_number = 10; // ⚠️ }

編譯器說:error[E0384]: cannot assign twice to immutable variable my_number。這是因為如果你只寫 let,變數是不可變的。

但有時你想更改你的變數。要建立一個可以改變的變數,就要在 let 後面加上 mut。

fn main() { let mut my_number = 8; my_number = 10; }

現在就沒問題了。

但是,你不能改變型別:即使加上 mut 也做不到。這樣將會無法編譯:

fn main() { let mut my_variable = 8; // 它現在是 i32. 型別不能被改變 my_variable = "Hello, world!"; // ⚠️ }

你會看到編譯器發出的同樣的"預期"訊息。expected integer, found &str。我們很快就會知道 &str 是一個字串型別。

遮蔽

遮蔽 (Shadowing) 是指使用 let 宣告與另一個變數同名的新變數。它看起來像可變性,但完全不同。遮蔽看起來像這樣:

fn main() { let my_number = 8; // 這是 i32 println!("{}", my_number); // 印出 8 let my_number = 9.2; // 這是同名的 f64。 但它已經不是第一個 my_number──它完全不一樣! println!("{}", my_number) // 印出 9.2 }

這裡我們會說我們用一個新的 "let 繫結(binding)" 對 my_number 進行了"遮蔽"。

那麼第一個 my_number 是否被銷毀了呢?沒有,但是當我們叫用 my_number 時,我們現在得到 f64 型別的 my_number。因為它們在同一個作用域區塊中(同一個 {}),我們無法再看到第一個 my_number 了。

但如果它們在不同的區塊中,我們可以同時看到兩者。例如:

fn main() { let my_number = 8; // 這是 i32 println!("{}", my_number); // 印出 8 { let my_number = 9.2; // 這是 f64。 它不是原先的 my_number──它完全不一樣! println!("{}", my_number) // 印出 9.2 // 但是被遮蔽的 my_number 只活到這裡。 // 原來的 my_number 還活著! } println!("{}", my_number); // 印出 8 }

因此,當你對一個變數遮蔽時,你不會銷毀它。你阻擋了它。

那麼遮蔽的好處是什麼呢?當你需要經常改變一個變數的時候,遮蔽很好用。想象你想用變數做很多簡單數學運算時:

fn times_two(number: i32) -> i32 { number * 2 } fn main() { let final_number = { let y = 10; let x = 9; // x 從 9 開始 let x = times_two(x); // 遮蔽後新的 x: 18 let x = x + y; // 遮蔽後新的 x: 28 x // 回傳 x: final_number 現在是 x 的值 }; println!("The number is now: {}", final_number) }

如果沒有遮蔽,你將要思考用什麼不同的名稱,即使你並不關心變數 x:

fn times_two(number: i32) -> i32 { number * 2 } fn main() { // Pretending we are using Rust without 遮蔽 let final_number = { let y = 10; let x = 9; // x 從 9 開始 let x_twice = times_two(x); // x 的第二個名字 let x_twice_and_y = x_twice + y; // x 的第三個名字! x_twice_and_y // 真糟糕沒有遮蔽可用──我們只要用 x 就好 }; println!("The number is now: {}", final_number) }

一般來說,你在 Rust 中看到的遮蔽就是這種情況。它發生在你想快速得對變數做一些事情,然後再做其他事情的地方。而你通常將它用在那些你不太關心的臨時變數上。

堆疊、堆積和指標

堆疊(stack)、堆積(heap)和指標(pointer)在 Rust 中非常重要。

堆疊和堆積是電腦中保存記憶體的兩個地方。主要的區別在:

- 堆疊的速度非常快,但堆積就不那麼快了。它也不是超慢,但堆疊總是更快。但是你不能一直使用堆疊,因為:

- Rust 在編譯時必需知道變數的大小。所以像

i32的簡單變數就放在堆疊上,因為我們知道它們的確切大小。你總是知道i32要 4 位元組,因為 32 位元 = 4 位元組。所以i32總是可以放在堆疊上。 - 但有些型別在編譯時不知道大小。但是堆疊需要知道確切的大小。那麼你該怎麼做呢?首先你把資料放在堆積中,因為堆積中可以有任何大小的資料。然後為了找到它,一個指標就會放上堆疊。這樣沒問題,因為我們總是知道指標的大小。所以,電腦就會先去堆疊讀取指標,然後跟著指標到資料所在的堆積。

指標聽起來很複雜,但它們很容易。指標就像一本書的目錄。想象一下這本書:

MY BOOK

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter Page

Chapter 1: My life 1

Chapter 2: My cat 15

Chapter 3: My job 23

Chapter 4: My family 30

Chapter 5: Future plans 43

所以這就像有五個指標。你可以閱讀它們,找到它們所說的資訊。"My life" 這一章在哪裡?它在第 1 頁(它 指向 第 1 頁)。"My job" 這一章在哪裡?它在第23頁。

通常在 Rust 中看到的指標稱做 參考。重點在於知道:一個參考指向另一個值的記憶體位置。參考意味著你 借 了這個值,但你並不擁有它。這和我們的書一樣:目錄並不擁有資訊。章節裡才有資訊。在 Rust 中,參考的前面有一個 &。所以:

let my_variable = 8是一個正規的變數,但是:let my_reference = &my_variable是一個變數參考。

你把 my_reference = &my_variable 讀成這樣:"my_reference 是對my_variable 的參考" 或者:"my_reference 參照到 my_variable"。

這意味著 my_reference 只看 my_variable 的資料。my_variable 仍然擁有它的資料。

你也可以有一個參考的參考,或者任何數量的參考。

fn main() { let my_number = 15; // 這是 i32 let single_reference = &my_number; // 這是 &i32 let double_reference = &single_reference; // 這是 &&i32 let five_references = &&&&&my_number; // 這是 &&&&&i32 }

這些都是不同的型別,就像 "朋友的朋友"和 "朋友"不同一樣。

更多關於列印

在 Rust 中,你幾乎可以用任何你想要的方式列印東西。這裡可以知道更多關於列印的事情。

加入 \n 將會產生一個新行(newline),而 \t 將會產生定位字元(tab):

fn main() { // Note: 這是 print!, 不是 println! print!("\t Start with a tab\nand move to a new line"); }

印出:

Start with a tab

and move to a new line

"" 裡面可以寫上許多行都沒有問題,但是要注意間距:

fn main() { // Note: 第一行後你要從最左邊開始。 // 如果你直接寫在 println! 下面,它會加入開頭的空白 println!("Inside quotes you can write over many lines and it will print just fine."); println!("If you forget to write on the left side, the spaces will be added when you print."); }

印出:

Inside quotes

you can write over

many lines

and it will print just fine.

If you forget to write

on the left side, the spaces

will be added when you print.

如果你想印出 \n 這樣的字元(稱為"跳脫字元"),你可以多加一個額外的 \。

fn main() { println!("Here are two escape characters: \\n and \\t"); }

印出:

Here are two escape characters: \n and \t

有時你有太多的 " 和跳脫字元,並希望 Rust 忽略所有要處理的東西。要做到這件事,你可以在開頭加上 r#,在結尾加上 #。

fn main() { println!("He said, \"You can find the file at c:\\files\\my_documents\\file.txt.\" Then I found the file."); // 這裡用了 \ 五次 println!(r#"He said, "You can find the file at c:\files\my_documents\file.txt." Then I found the file."#) }

這會印出一樣的東西,但是用 r# 使人更容易閱讀。

He said, "You can find the file at c:\files\my_documents\file.txt." Then I found the file.

He said, "You can find the file at c:\files\my_documents\file.txt." Then I found the file.

如果你需要在內容裡面印出 #,那麼你可以用 r## 開頭,用 ## 結尾。如果你要印超過一個 #,兩邊要再各多加一個 #。

這有四個範例:

fn main() { let my_string = "'Ice to see you,' he said."; // 單引號 let quote_string = r#""Ice to see you," he said."#; // 雙引號 let hashtag_string = r##"The hashtag #IceToSeeYou had become very popular."##; // 一個 # 所以我們至少要用 ## let many_hashtags = r####""You don't have to type ### to use a hashtag. You can just use #.""####; // 有三個 ### 所以我們至少要用 #### println!("{}\n{}\n{}\n{}\n", my_string, quote_string, hashtag_string, many_hashtags); }

會印出:

'Ice to see you,' he said.

"Ice to see you," he said.

The hashtag #IceToSeeYou had become very popular.

"You don't have to type ### to use a hashtag. You can just use #."

r# 還有另一個用途:你能用它來把關鍵字(如 let、fn 等)當作變數名稱。

fn main() { let r#let = 6; // 變數名是 let let mut r#mut = 10; // 變數名是 mut }

r# 之所以有這個功能,是因為舊版的 Rust 關鍵字比現在的少。所以有了 r# 以前不是關鍵字的變數名就能避免出錯。

又或者因為某些原因,你 確實 需要一個名字像是 return 的函式。那麼你可以這樣寫:

fn r#return() -> u8 { println!("Here is your number."); 8 } fn main() { let my_number = r#return(); println!("{}", my_number); }

印出:

Here is your number.

8

所以你大概不會需要它,但是如果你真的需要用關鍵字當變數,那就用 r#。

如果你想印出 &str 或 char 的位元組,你可以在字串前寫上 b 就可以了。這適用於所有 ASCII 字元。以下這些是所有的 ASCII 字元:

☺☻♥♦♣♠♫☼►◄↕‼¶§▬↨↑↓→∟↔▲▼123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~

所以,當你印出這個程式:

fn main() { println!("{:?}", b"This will look like numbers"); }

結果是這樣:

[84, 104, 105, 115, 32, 119, 105, 108, 108, 32, 108, 111, 111, 107, 32, 108, 105, 107, 101, 32, 110, 117, 109, 98, 101, 114, 115]

對 char 來說,這叫做 位元組,對 &str 來說,這叫做 位元組字串。

如果有需要,你也可以把 b 和 r 放在一起:

fn main() { println!("{:?}", br##"I like to write "#"."##); }

它會印出 [73, 32, 108, 105, 107, 101, 32, 116, 111, 32, 119, 114, 105, 116, 101, 32, 34, 35, 34, 46]。

還有一個 Unicode 轉義(escape),可以讓你在字串中印出任何 Unicode 字元:\u{}。{} 裡面要有一個可以列印的十六進位制數字。這個是說明如何獲得 Unicode 數字及如何再把它印出來的簡短例子。

fn main() { println!("{:X}", '행' as u32); // char 轉型 u32 來取得十六進位值 println!("{:X}", 'H' as u32); println!("{:X}", '居' as u32); println!("{:X}", 'い' as u32); println!("\u{D589}, \u{48}, \u{5C45}, \u{3044}"); // 試著以 unicode 轉義 \u 印出它們 }

我們知道 println! 可以用 {}(用於顯示) 或 {:?}(用於除錯) 來列印,再加上 {:#?} 可以進行漂亮列印。但是還有許多其他列印方式。

例如,如果你有一個變數參考,你可以用 {:p} 來印出 指標地址。指標地址指的是電腦記憶體中的位置。

fn main() { let number = 9; let number_ref = &number; println!("{:p}", number_ref); }

這會印出 0xe2bc0ffcfc 或者其它地址。它可能每次都不一樣,這取決於你的電腦在哪裡儲存它。

或者你可以列印二進位、十六進位和八進位的值:

fn main() { let number = 555; println!("Binary: {:b}, hexadecimal: {:x}, octal: {:o}", number, number, number); }

印出了 Binary: 1000101011, hexadecimal: 22b, octal: 1053。

或者你可以加上數字來改變順序。第一個變數將在索引0 中,下一個在索引1 中,以此類推。

fn main() { let father_name = "Vlad"; let son_name = "Adrian Fahrenheit"; let family_name = "Țepeș"; println!("This is {1} {2}, son of {0} {2}.", father_name, son_name, family_name); }

father_name 在位置0,son_name 在位置1,family_name 在位置2。所以它印出的是 This is Adrian Fahrenheit Țepeș, son of Vlad Țepeș。

也許你有一個非常複雜的字串要列印,有太多的變數要放在 {} 括號內。或者你需要印同一個變數不止一次。那麼在 {} 裡加上變數名就幫得上忙:

fn main() { println!( "{city1} is in {country} and {city2} is also in {country}, but {city3} is not in {country}.", city1 = "Seoul", city2 = "Busan", city3 = "Tokyo", country = "Korea" ); }

這樣會印出:

Seoul is in Korea and Busan is also in Korea,

but Tokyo is not in Korea.

在Rust中也可以進行非常複雜的列印,如果你想的話。這裡看到它是如何做到的:

{variable:padding alignment minimum.maximum}

要理解這個語法,看以下規則

- 你想要有變數名嗎?先寫出來,就像我們上面寫 {country} 一樣。

(如果你想做更多事,就在後面加一個

:) - 你想要用填充字元嗎?例如,55 加上三個 "填充零" 就像 00055。

- 填充的對齊方式(左/中/右)?

- 你想要有最小長度嗎?(寫數字就行)

- 你想要有最大長度嗎?(寫數字,前面有個

.)

例如,我想寫 "a",在它左邊有五個 ㅎ,在它右邊有五個 ㅎ:

fn main() { let letter = "a"; println!("{:ㅎ^11}", letter); }

這印出來是 ㅎㅎㅎㅎㅎaㅎㅎㅎㅎㅎ。我們看看 1) 到 5) 怎麼解釋這個情況,就能明白編譯器是怎麼解讀的:

- 你要不要變數名?

{:ㅎ^11}沒有變數名。:之前沒有任何內容。 - 你需要填充字元嗎?

{:ㅎ^11}是。ㅎ 在:後面,還有一個^。<表示變數在填充字元左邊,>表示在填充字元右邊,^表示在填充字元中間。 - 要不要設定最小長度?

{:ㅎ^11}是:後面有一個 11。 - 要不要設定最大長度?

{:ㅎ^11}不是:前面沒有.的數字。

下面是許多種型別格式化的例子:

fn main() { let title = "TODAY'S NEWS"; println!("{:-^30}", title); // 沒變數名, 用-填充, 放中間, 30個字元長 let bar = "|"; println!("{: <15}{: >15}", bar, bar); // 沒變數名, 用空白填充, 各是15個字元長, 一左一右 let a = "SEOUL"; let b = "TOKYO"; println!("{city1:-<15}{city2:->15}", city1 = a, city2 = b); // 變數city1和city2, 用-填充, 一左一右 }

印出:

---------TODAY'S NEWS---------

| |

SEOUL--------------------TOKYO

字串

Rust 的字串主要型別有兩類:String 和 &str。有什麼差別呢?

&str是種簡單的字串。當你寫let my_variable = "Hello, world!"時,你建立的是一個&str。&str建立非常快。String是比較復雜的字串。它比較慢一點,但它有更多的功能。String是一個指標,資料在堆積上。

另外注意,&str 前面有 &,因為你需要一個參考來使用 str。這是因為我們先前看到的原因:堆疊需要知道資料大小。所以我們給它一個它知道大小的 &,然後它就滿意了。另外,因為你是用 & 去和 str 互動,你並不擁有它。但是 String 是一個 擁有所有權 的型別。我們很快就會知道為什麼這一點很重要。

&str 和String 都是UTF-8。例如,你可以寫:

fn main() { let name = "서태지"; // 這是韓國名字。沒問題,因為 &str 是 UTF-8。 let other_name = String::from("Adrian Fahrenheit Țepeș"); // UTF-8 的 Ț 和 ș 沒問題。 }

你可以在 String::from("Adrian Fahrenheit Țepeș") 中看到,從 &str 中建立 String 很容易。這兩種型別雖然不同,但彼此聯繫非常緊密。

你甚至可以寫表情符號,這要感謝 UTF-8。

fn main() { let name = "😂"; println!("My name is actually {}", name); }

在你的電腦上,會印出 My name is actually 😂,除非你的命令列印不出(Unicode字元)。那麼它會顯示 My name is actually �。但 Rust 對 emojis 或其他 Unicode (處理上)沒有問題。

我們再來看看 str 使用 & 的原因,以確保我們有理解。

str是一個動態大小(dynamically sized)的型別(動態大小 = 大小可以不同)。比如 "서태지" 和 "Adrian Fahrenheit Țepeș" 這兩個名字的大小是不一樣的:

fn main() { println!("A String is always {:?} bytes. It is Sized.", std::mem::size_of::<String>()); // std::mem::size_of::<Type>() 給你型別的位元組單位大小 println!("And an i8 is always {:?} bytes. It is Sized.", std::mem::size_of::<i8>()); println!("And an f64 is always {:?} bytes. It is Sized.", std::mem::size_of::<f64>()); println!("But a &str? It can be anything. '서태지' is {:?} bytes. It is not Sized.", std::mem::size_of_val("서태지")); // std::mem::size_of_val() 給你變數的位元組單位大小 println!("And 'Adrian Fahrenheit Țepeș' is {:?} bytes. It is not Sized.", std::mem::size_of_val("Adrian Fahrenheit Țepeș")); }

列出:

A String is always 24 bytes. It is Sized.

And an i8 is always 1 bytes. It is Sized.

And an f64 is always 8 bytes. It is Sized.

But a &str? It can be anything. '서태지' is 9 bytes. It is not Sized.

And 'Adrian Fahrenheit Țepeș' is 25 bytes. It is not Sized.

這就是為什麼我們需要一個 &,因為 & 建立一個指標,而 Rust 知道指標的大小。所以指標會放在堆疊中。如果我們寫的是 str,Rust 因為不知道大小就不曉得該怎麼做了。

有很多方法可以建立 String。這裡是其中一些:

String::from("This is the string text");這是 String 型別用文字建立 String 的方法。"This is the string text".to_string()。 這是 &str 型別用來做出 String 的方法。format!巨集。 像是println!,只不過它是建立 String,而不是列印。所以你可以這樣做:

fn main() { let my_name = "Billybrobby"; let my_country = "USA"; let my_home = "Korea"; let together = format!( "I am {} and I come from {} but I live in {}.", my_name, my_country, my_home ); }

現在我們有了名為 together 的 String,但還沒有印出來。

還有一種建立 String 的方法叫做 .into(),但它有點不同,因為 .into() 並不只是用來建立 String。有些型別可以很容易地使用 From 和 .into() 來回轉換為另一種型別。而如果你有 From,那麼你也有 .into()。From 更加清晰,因為你已經知道了型別:你知道 String::from("Some str") 是來自 &str 的 String。但是對於 .into(),有時候編譯器並不知道:

fn main() { let my_string = "Try to make this a String".into(); // ⚠️ }

Rust 不知道你要的是什麼型別,因為很多型別都可以由 &str 來組成。它說:"我可以把 &str 變成很多東西。你想要哪一種?"

error[E0282]: type annotations needed

--> src\main.rs:2:9

|

2 | let my_string = "Try to make this a String".into();

| ^^^^^^^^^ consider giving `my_string` a type

所以你可以這樣做:

fn main() { let my_string: String = "Try to make this a String".into(); }

現在你得到 String 了。

const 和 static

有兩種宣告值的方法,不僅僅是用 let。它們是 const 和 static。另外,Rust 不會使用型別推理:你需要為它們編寫型別。這些都是用於不改變的值(const 表示常數)。區別在於:

const是用於不改變的值,當使用它時,名字會被替換成值。static與const類似,但有一個固定的記憶體位置,可以作為一個全域性變數使用。

所以它們幾乎是一樣的。Rust 程式設計師幾乎總是使用 const。

你用全大寫字母命名,而且通常放在 main 之外,這樣它們就可以在整個程式中生存。

兩個範例是 const NUMBER_OF_MONTHS: u32 = 12; 和 static SEASONS: [&str; 4] = ["Spring", "Summer", "Fall", "Winter"];

更多關於參考

參考在 Rust 中非常重要。Rust 使用參考來確保所有的記憶體訪問是安全的。我們知道,我們用 & 來建立參考:

fn main() { let country = String::from("Austria"); let ref_one = &country; let ref_two = &country; println!("{}", ref_one); }

這樣會印出 Austria。

在程式碼中,country 是 String。我們接著建立了兩個 country 的參考。它們的型別是 &String,你會講說這是 "String 的參考"。我們可以建立三個參考或者一百個對 country 的參考,這都沒有問題。

但這裡有問題:

fn return_str() -> &str { let country = String::from("Austria"); let country_ref = &country; country_ref // ⚠️ } fn main() { let country = return_str(); }

return_str() 函式建立了 String,它接著建立了對這個 String 的參考。然後它試圖回傳參考。但是 country 這個 String 只活在函式里面,然後它就死了。一旦變數消失了,電腦就會清理記憶體,並將其用於其他用途。所以在函式結束後,country_ref 參考到的是已經消失的記憶體,這是不對的。Rust 防止我們在這裡犯記憶體的錯誤。

這就是我們前面講到的 "擁有所有權" 型別的重要部分。因為你擁有 String,你可以把它傳給別人。但是如果 &String 的 String 死了,那麼 &String 就會死掉,所以你不能把它的 "所有權" 傳給別人。

可變參考

如果你想使用參考來改變資料,你可以使用可變參考(mutable reference)。可變參考你要寫做 &mut 而不是 &。

fn main() { let mut my_number = 8; // 這裡不要忘記寫 mut! let num_ref = &mut my_number; }

那麼這兩種型別是什麼呢?my_number 是 i32,而 num_ref 是 &mut i32(我們讀作 "可變參考 i32")。

那麼讓我們用它來給 my_number 加上 10。但是你不能寫 num_ref += 10,因為 num_ref 不是 i32 的值,它是 &i32。其實這個值就在 i32 裡面。為了達到值所在的地方,我們用 *。* 的意思是"我不要參考,我想要參考所參照的值"。換句話說,* 與 & 是相反的動作。也就是一個 * 消去了一個 &。

fn main() { let mut my_number = 8; let num_ref = &mut my_number; *num_ref += 10; // 使用 * 來改變 i32 的值. println!("{}", my_number); let second_number = 800; let triple_reference = &&&second_number; println!("Second_number = triple_reference? {}", second_number == ***triple_reference); }

印出:

18

Second_number = triple_reference? true

因為使用 & 時叫做 "參考",所以用 * 叫做 "反參考(dereferencing)"。

Rust在可變和不可變參考有兩個規則。它們非常重要卻也容易記住,因為它們很有道理。

- 規則1:如果你只有不可變參考,你可以同時有任意多的參考。1 個也好,3 個也好,1000 個也好,都沒問題。

- 規則2:如果是可變參考,你只能有一個。另外,你不能同時有一個不可變參考和一個可變參考。

這是因為可變參考能變更資料。如果你在其他參考讀取資料時更改資料,你可能會遇到問題。

理解的好方法是設想一場 Powerpoint 簡報。

情境一是關於只有一個可變參考。

情境一: 一位員工正在編寫一個 Powerpoint 簡報,他希望他的經理能幫助他。該員工將自己的登入資訊提供給經理,並請他幫忙進行編輯。現在經理對該員工的簡報有了"可變參考"。經理可以做任何他想做的修改,然後把電腦還回去。這很好,因為沒有其他人看得到這個簡報。

情境二是關於只有不可變參考。

情境二: 該員工要給100個人做簡報。現在這100個人都可以看到該員工的資料。他們全都有對該員工簡報的"不可變參考"。這很好,因為他們可以看得到,但沒人可以改動資料。

情境三是有問題的情形

情境三: 員工把他的登入資訊給了經理 他的經理現在有了一個 "可變參考"。然後該員工去給 100 個人做簡報,但是經理還是可以登入。這是不對的,因為經理可以登入,可以做任何事情。也許他的經理會登入電腦,然後開始給他的母親打一封信!現在這 100 人不得不看著經理給他母親寫信,而不是簡報。這不是他們期望看到的。

這裡有一個可變借用借用自不可變借用的範例:

fn main() { let mut number = 10; let number_ref = &number; let number_change = &mut number; *number_change += 10; println!("{}", number_ref); // ⚠️ }

編譯器印出了一則有用的資訊來告訴我們問題所在。

error[E0502]: cannot borrow `number` as mutable because it is also borrowed as immutable

--> src\main.rs:4:25

|

3 | let number_ref = &number;

| ------- immutable borrow occurs here

4 | let number_change = &mut number;

| ^^^^^^^^^^^ mutable borrow occurs here

5 | *number_change += 10;

6 | println!("{}", number_ref);

| ---------- immutable borrow later used here

然而,這段程式碼可以運作。為什麼?

fn main() { let mut number = 10; let number_change = &mut number; // 建立可變借用 *number_change += 10; // 用可變借用來加上 10 let number_ref = &number; // 建立不可變借用 println!("{}", number_ref); // 印出不可變借用 }

它印出 20 沒有問題。它能運作是因為編譯器夠聰明,能理解我們的程式碼。它知道我們使用了 number_change 來改變 number,但沒有再使用它。所以這裡沒有問題。我們並沒有將不可變和可變參考一起使用。

早期在 Rust 中,這種程式碼實際上會產生錯誤,但現在的編譯器更聰明了。它不僅能理解我們輸入的內容,還能理解我們如何使用所有的東西。

再談遮蔽

還記得我們說過,遮蔽(shadowing)不會銷毀一個值,而是阻擋它嗎?現在我們可以用參考來看這個問題。

fn main() { let country = String::from("Austria"); let country_ref = &country; let country = 8; println!("{}, {}", country_ref, country); }

這會印出 Austria, 8 還是 8, 8?它印出的是 Austria, 8。首先我們宣告一個 String,叫做 country。然後我們給這個字串建立一個參考 country_ref。然後我們用 8,這是 i32,來遮蔽 country。但是第一個 country 並沒有被銷毀,所以 country_ref 仍然參照著 "Austria",而不是 "8"。這是同樣的程式碼附上了一些註解來說明它如何運作:

fn main() { let country = String::from("Austria"); // 現在我們有個 String 叫作 country let country_ref = &country; // country_ref 是這筆資料的參考。它不會改動 let country = 8; // 現在我們有個變數叫作 country 型別是 i8。但它和另一個變數或 country_ref 沒有關聯 println!("{}, {}", country_ref, country); // country_ref 仍然參照自我們給的 String::from("Austria") 的資料. }

傳遞參考給函式

參考對函式非常有用。Rust 中關於值的規則是:一個值只能有一個所有者。

這段程式碼將無法運作:

fn print_country(country_name: String) { println!("{}", country_name); } fn main() { let country = String::from("Austria"); print_country(country); // 我們印出 "Austria" print_country(country); // ⚠️ 蠻有趣的,讓我們再做一次! }

它不能運作,因為 country 被銷毀了。它是這麼來的:

- 第一步:我們建立稱為

country的String。country是所有者。 - 第二步:我們把

country給了print_country。print_country沒有->,所以它不回傳任何東西。在print_country完成後,我們的String現在已經死了。 - 第三步:我們嘗試把

country給print_country,但我們已經這樣做過了。我們已經沒有country可以給了。

我們可以讓 print_country 給回 String,但是有點奇怪。

fn print_country(country_name: String) -> String { println!("{}", country_name); country_name // 這裡回傳它 } fn main() { let country = String::from("Austria"); let country = print_country(country); // 我們現在要在這裡用 let 拿回 String print_country(country); }

現在印出了:

Austria

Austria

更好的解決方式是加上 &。

fn print_country(country_name: &String) { println!("{}", country_name); } fn main() { let country = String::from("Austria"); print_country(&country); // 我們印出 "Austria" print_country(&country); // 蠻有趣的,讓我們再做一次! }

現在 print_country() 是一個函式,接受 String 的參考:即 &String。另外,我們寫 &country 來給 country 一個參考,。這表示 "你可以查看它,但我會保有它"。

現在讓我們用一個可變參考來做類似的事情。這是個使用可變變數的函式範例:

fn add_hungary(country_name: &mut String) { // 首先我們說函式接受一個可變參考 country_name.push_str("-Hungary"); // push_str() 加入 &str 到 String println!("Now it says: {}", country_name); } fn main() { let mut country = String::from("Austria"); add_hungary(&mut country); // 我們也要給它可變參考。 }

這印出了 Now it says: Austria-Hungary。

所以得出結論:

fn function_name(variable: String)接受String並擁有它。如果它不回傳任何東西,那麼這個變數就會死在函數裡面。fn function_name(variable: &String)借用String並可以查看它fn function_name(variable: &mut String)借用String並可以更改

這是個看起來像可變參考但不同的範例。

fn main() { let country = String::from("Austria"); // country 是不可變的,但我們想要印出 Austria-Hungary。怎麼做? adds_hungary(country); } fn adds_hungary(mut country: String) { // 它是這樣做的:adds_hungary 接受 String 並宣告它是可變的! country.push_str("-Hungary"); println!("{}", country); }

這怎麼可能呢?因為 mut country 不是參考。adds_hungary 現在擁有 country。(記得,它接受的是 String 而不是 &String)。當你呼叫 adds_hungary 的那一刻,它就完全成了 country 的所有者。country 與 String::from("Austria") 沒有關係了。所以,adds_hungary 可以把 country 當作可變的,這樣做是完全安全的。

還記得前面我們的員工 Powerpoint 和經理的情況嗎?在這種情況下,就好比員工只是把自己的整臺電腦交給了經理。員工不會再碰它,所以經理可以對它做任何他想做的事情。

複製型別

Rust 中的一些型別非常簡單。它們被稱為複製型別。這些簡單型別都在堆疊上,編譯器知道它們的大小。這意味著它們非常容易複製,所以當你把它傳送到函式時,編譯器永遠會用複製的方式。它永遠會複製,是因為它們如此的小而容易到沒有理由不複製。所以你不需要擔心這些型別的所有權問題。

這些簡單的型別包括:整數、浮點數、布林值(true 和 false)和 char。

如何知道一個型別是否實作複製?(實作 = 能夠使用)你可以檢查文件。例如,這是 char 的文件:

https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/primitive.char.html

在左邊你可以看到 Trait Implementations。例如你可以看到 Copy, Debug, 和 Display。所以你知道 char型別:

- 當傳送到函式時就被複制了 (Copy)

- 可以用

{}列印 (Display) - 可以用

{:?}列印 (Debug)

fn prints_number(number: i32) { // 沒有 -> 所以不回傳任何東西 // 如果數字不是複製型別,它會拿走資料 // 我們也不能再拿來用 println!("{}", number); } fn main() { let my_number = 8; prints_number(my_number); // 印出 8。prints_number 得到 my_number 的拷貝 prints_number(my_number); // 又印出 8。 // 沒問題,因為 my_number 是複製型別! }

但是如果你有看到 String 的文件,它不是複製型別。

https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/string/struct.String.html

在左邊的 Trait Implementations 中,你可以按字母順序查詢。A、B、C......在 C 裡面沒有 Copy,但是有 Clone。Clone 和 Copy 類似,但通常需要更多的記憶體。另外,你必須用 .clone() 來呼叫它──它不會為自己克隆(clone)。

在這個範例中,prints_country() 印出國家名稱,是個 String。我們想印兩次,但沒辦法:

fn prints_country(country_name: String) { println!("{}", country_name); } fn main() { let country = String::from("Kiribati"); prints_country(country); prints_country(country); // ⚠️ }

但現在我們懂這個訊息了。

error[E0382]: use of moved value: `country`

--> src\main.rs:4:20

|

2 | let country = String::from("Kiribati");

| ------- move occurs because `country` has type `std::string::String`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

3 | prints_country(country);

| ------- value moved here

4 | prints_country(country);

| ^^^^^^^ value used here after move

重點是 which does not implement the Copy trait。但在文件中我們看到 String 實現了 Clone 特徵。所以我們可以把 .clone() 加到我們的程式碼中。這樣就建立了一個克隆,然後我們將克隆傳送到函式中。現在 country 還活著,所以我們可以使用它。

fn prints_country(country_name: String) { println!("{}", country_name); } fn main() { let country = String::from("Kiribati"); prints_country(country.clone()); // 做一個克隆並傳遞給函式。只有克隆送進去,且 country 仍然還活著 prints_country(country); }

如果 String 非常大,當然 .clone() 就會佔用很多記憶體。一個 String 可以是一整本書的長度,每次我們呼叫 .clone() 都會複製這本書。所以這時如果可以用 & 來做參考的話會比較快。例如,這段程式碼將 &str 推送到 String 上,然後每次被使用在函式時都會做一個克隆:

fn get_length(input: String) { // 接收String的所有權 println!("It's {} words long.", input.split_whitespace().count()); // 分開算字數 } fn main() { let mut my_string = String::new(); for _ in 0..50 { my_string.push_str("Here are some more words "); // 推送字句 get_length(my_string.clone()); // 每次給它一份克隆 } }

印出:

It's 5 words long.

It's 10 words long.

...

It's 250 words long.

這樣是 50 次克隆。這裡用參考代替更好:

fn get_length(input: &String) { println!("It's {} words long.", input.split_whitespace().count()); } fn main() { let mut my_string = String::new(); for _ in 0..50 { my_string.push_str("Here are some more words "); get_length(&my_string); } }

0 次克隆,而不是 50 次。

無值變數

一個沒有值的變數叫做"未初始化"變數。未初始化的意思是"還沒有開始"。它們很簡單:只需要寫上 let 和變數名:

fn main() { let my_variable; // ⚠️ }

但是你還不能使用它,如果有任何東西沒有被初始化 Rust 不會開始編譯。

但有時它們會很有用。一個好範列是:

- 當你有一個程式碼區塊,而你的變數值就在裡面,並且

- 變數需要活在程式碼區塊之外。

fn loop_then_return(mut counter: i32) -> i32 { loop { counter += 1; if counter % 50 == 0 { break; } } counter } fn main() { let my_number; { // 假裝我們需要這個程式碼區塊 let number = { // 假裝這有程式碼產生數字 // 滿滿的程式,終於: 57 }; my_number = loop_then_return(number); } println!("{}", my_number); }

印出 100。

你可以看到 my_number 是在 main() 函式中宣告的,所以它一直活到最後。但是它的值是在迴圈裡面得到的。然而,這個值和 my_number 活得一樣長,因為 my_number 擁有這個值。而如果你在區塊裡面寫了 let my_number = loop_then_return(number),它就會馬上死掉。

如果你簡化程式碼,有助於想像這個概念。loop_then_return(number) 給出的結果是 100,所以我們刪除它,改寫 100。另外,現在我們不需要 number,所以我們也刪除它。現在它看起來像這樣:

fn main() { let my_number; { my_number = 100; } println!("{}", my_number); }

所以和說 let my_number = { 100 }; 差不多。

另外注意,my_number 不是 mut。我們在給它 50 之前並沒有給它一個值,所以它的值不曾改變過。最後,my_number 的真正程式碼只是 let my_number = 100;。

集合型別

Rust 有許多型別用來做出集合(collection)。集合是在某個地方你需要有超過一個值時用的。例如,你可以在一個變數中包含你所在國家的所有城市資訊。我們會先從陣列(array)開始,它的速度最快,但功能也最少。在這方面它們有點像 &str。

陣列

陣列是放在中括號裡的資料:[]。陣列特性:

- 不能改變其大小,

- 必須只包含相同型別資料。

然而它們的速度卻非常快。

陣列的型別是:[type; number]。例如,["One", "Two"] 的型別是 [&str; 2]。這意味著,即使這兩個是陣列也有不同的型別:

fn main() { let array1 = ["One", "Two"]; // 這個型別是 [&str; 2] let array2 = ["One", "Two", "Five"]; // 但這個型別是 [&str; 3]。不同型別! }

這裡有個好提示:要想知道變數的型別,你可以藉由給編譯器不正確的程式碼來"詢問"它。比如說:

fn main() { let seasons = ["Spring", "Summer", "Autumn", "Winter"]; let seasons2 = ["Spring", "Summer", "Fall", "Autumn", "Winter"]; seasons.ddd(); // ⚠️ seasons2.thd(); // 還是⚠️ }

編譯器說:"什麼?seasons 沒有 .ddd() 的方法,seasons2 也沒有 .thd() 的方法!!" 你可以看到:

error[E0599]: no method named `ddd` found for array `[&str; 4]` in the current scope

--> src\main.rs:4:13

|

4 | seasons.ddd(); //

| ^^^ method not found in `[&str; 4]`

error[E0599]: no method named `thd` found for array `[&str; 5]` in the current scope

--> src\main.rs:5:14

|

5 | seasons2.thd(); //

| ^^^ method not found in `[&str; 5]`

所以它告訴你 method not found in `[&str; 4]`,這就是變數的型別。

如果你想要一個數值都一樣的陣列,你可以像這樣宣告:

fn main() { let my_array = ["a"; 10]; println!("{:?}", my_array); }

這裡印出 ["a", "a", "a", "a", "a", "a", "a", "a", "a", "a"]。

這個方法經常用來建立緩衝區(buffer)。例如,let mut buffer = [0; 640] 建立一個 640 個零的陣列。然後我們可以將零改為其他數字,以便新增資料。

你可以用 [] 來索引(獲取)陣列中的項目。第一個索引項目是 [0],第二個是 [1],以此類推。

fn main() { let my_numbers = [0, 10, -20]; println!("{}", my_numbers[1]); // 印出 10 }

你可以得到陣列的一個切片(slice,一塊)。首先你需要 &,因為編譯器不知道大小。然後你可以使用 .. 來表示範圍。

例如,讓我們使用這個陣列:[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]。

fn main() { let array_of_ten = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]; let three_to_five = &array_of_ten[2..5]; let start_at_two = &array_of_ten[1..]; let end_at_five = &array_of_ten[..5]; let everything = &array_of_ten[..]; println!("Three to five: {:?}, start at two: {:?}, end at five: {:?}, everything: {:?}", three_to_five, start_at_two, end_at_five, everything); }

記住這些:

- 索引號從 0 開始(不是 1)

- 索引範圍是排除的(不包括最後一個數字)。

所以 [0..2] 是指第一項索引和第二項索引(0 和 1)。或者你也可以稱它為"第零和第一項"索引。它沒有第三項,也就是索引 2。

你也可以有一個 包含的 範圍,這意味著它也包括最後一個數字。要做到這一點。加上 =,寫成 ..=,而不是 ..。所以,如果你想要第一、第二和第三項,可以寫成 [0..=2],而不是 [0..2]。

向量

就像我們有 &str 和 String 一樣的方式,我們有陣列和向量(vector)。陣列的功能少了就快,向量的功能多了就慢。(當然,Rust 的速度一直都是非常快的,所以向量並不慢,只是比陣列慢一點)。型別被寫作 Vec,你也可以直接叫它 "vec"。

向量的宣告主要有兩種方式。一種像 String 使用 new:

fn main() { let name1 = String::from("Windy"); let name2 = String::from("Gomesy"); let mut my_vec = Vec::new(); // 如果我們現在就跑程式,編譯器會給出錯誤。 // 它不知道vec的型別。 my_vec.push(name1); // 現在它知道了:它是Vec<String> my_vec.push(name2); }

你可以看到 Vec 裡面總是有其他東西,這就是 <>(角括號)的作用。Vec<String>是有一或多個 String 的向量。你還可以在裡面有更多的型別。舉例來說:

Vec<(i32, i32)>這個Vec的每個元素是元組(tuple):(i32, i32)。Vec<Vec<String>>這個Vec裡面有包含String的Vec。假設說你想把你喜歡的書保存在Vec<String>。然後你再拿另一本書重做一次,就會得到另一個Vec<String>。為了保留這兩本書,你會把它們放入另一個Vec中,這就是Vec<Vec<String>>。

與其使用 .push() 讓 Rust 決定型別,不如直接宣告型別。

fn main() { let mut my_vec: Vec<String> = Vec::new(); // 編譯器知道型別 // 所以沒有錯誤。 }

你可以看到,向量中的元素必須具有相同的型別。

建立向量的另一個簡單方法是使用 vec! 巨集。它看起來像一個陣列宣告,但前面有 vec!。

fn main() { let mut my_vec = vec![8, 10, 10]; }

型別是 Vec<i32>。你稱它為 "i32 的 Vec"。而 Vec<String> 是 "String 的 Vec"。Vec<Vec<String>> 是 "String 的 Vec 的 Vec"。

你也可以對一個向量進行切片,就像用在陣列一樣。

fn main() { let vec_of_ten = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]; // 所有東西都和前面的陣列一樣,除了我們加上vec!。 let three_to_five = &vec_of_ten[2..5]; let start_at_two = &vec_of_ten[1..]; let end_at_five = &vec_of_ten[..5]; let everything = &vec_of_ten[..]; println!("Three to five: {:?}, start at two: {:?} end at five: {:?} everything: {:?}", three_to_five, start_at_two, end_at_five, everything); }

因為向量比陣列慢,我們可以用一些方法讓它更快。向量都有容量(capacity),也就是給予向量使用的空間。當你在向量上推送一個新元素時,它會越來越接近容量。然後,如果你超過了容量,它將使其容量翻倍,並將元素複製到新的空間。這就是所謂的再分配(reallocation)。我們將使用名為 .capacity() 的方法,在我們向它新增元素時來查看向量的容量。

例如:

fn main() { let mut num_vec = Vec::new(); println!("{}", num_vec.capacity()); // 0 個元素: 印出 0 num_vec.push('a'); // 加人一個字元 println!("{}", num_vec.capacity()); // 1 個元素: 印出 4. 一筆資料的 Vec 容量永遠從 4 開始 num_vec.push('a'); // 多加一個 num_vec.push('a'); // 多加一個 num_vec.push('a'); // 多加一個 println!("{}", num_vec.capacity()); // 4 個元素: 仍印出 4. num_vec.push('a'); // 多加一個 println!("{}", num_vec.capacity()); // 印出 8. 我們有 5 個元素, 但容量從 4 加倍到 8 騰出了空間 }

印出:

0

4

4

8

所以這個向量再分配兩次:0 到 4,4 到 8。我們可以讓它更快:

fn main() { let mut num_vec = Vec::with_capacity(8); // 給它容量 8 num_vec.push('a'); // 加一個字元 println!("{}", num_vec.capacity()); // 印出 8 num_vec.push('a'); // 再加一個 println!("{}", num_vec.capacity()); // 印出 8 num_vec.push('a'); // 再加一個 println!("{}", num_vec.capacity()); // 印出 8. num_vec.push('a'); // 再加一個 num_vec.push('a'); // 再加一個 // 現在我們有 5 個元素 println!("{}", num_vec.capacity()); // 仍是 8 }

這個向量比較好再分配是 0 次。所以如果你認為你知道你需要多少元素,你可以使用 Vec::with_capacity() 來使它更快。

你記得你可以用 .into() 把 &str 變成 String。你也可以用它把一個陣列變成 Vec。你必須告訴 .into() 你想要 Vec,但你可以不用選擇 Vec 的型別。如果你不想選擇,你可以寫 Vec<_>。

fn main() { let my_vec: Vec<u8> = [1, 2, 3].into(); let my_vec2: Vec<_> = [9, 0, 10].into(); // Vec<_> 表示 "幫我選 Vec 的型別" // Rust 會選 Vec<i32> }

元組

Rust 中的元組(tuple)使用 () 表示。我們已經見過很多空元組了,因為函式中的 nothing 實際上意味著一個空元組:

fn do_something() {}

其實是這個的簡寫:

fn do_something() -> () {}

這個函式什麼也得不到(空元組),也不回傳什麼(空元組)。所以我們已經經常使用元組了。當你在函式中不回傳任何東西時,你實際上回傳的是空元組。

fn just_prints() { println!("I am printing"); // 加上 ; 表示我們回傳空元組 } fn main() {}

但是元組可以容納很多東西,也可以容納不同的型別。元組裡面的元素也是用數字 0、1、2 等來被索引的。但要存取它們,你要用 . 而不是 []。讓我們把一大群型別放進元組裡。

fn main() { let random_tuple = ("Here is a name", 8, vec!['a'], 'b', [8, 9, 10], 7.7); println!( "Inside the tuple is: First item: {:?} Second item: {:?} Third item: {:?} Fourth item: {:?} Fifth item: {:?} Sixth item: {:?}", random_tuple.0, random_tuple.1, random_tuple.2, random_tuple.3, random_tuple.4, random_tuple.5, ) }

印出:

Inside the tuple is: First item: "Here is a name"

Second item: 8

Third item: ['a']

Fourth item: 'b'

Fifth item: [8, 9, 10]

Sixth item: 7.7

這個元組的型別是 (&str, i32, Vec<char>, char, [i32; 3], f64)。

你可以使用一個元組來建立多個變數。看看這段程式碼:

fn main() { let str_vec = vec!["one", "two", "three"]; }

str_vec 裡面有三個元素。如果我們想把它們拉出來呢?這時我們可以使用元組。

fn main() { let str_vec = vec!["one", "two", "three"]; let (a, b, c) = (str_vec[0], str_vec[1], str_vec[2]); // 叫它們 a, b, 和 c println!("{:?}", b); }

它印出 "two",也就是 b。這就是所謂的解構(destructuring)。這是因為變數一開始是在結構體裡面的,但接著我們又做了 a、b、c 這些不是在結構體裡面的變數。

如果你需要解構,但又不想要所有的變數,你可以使用 _。

fn main() { let str_vec = vec!["one", "two", "three"]; let (_, _, variable) = (str_vec[0], str_vec[1], str_vec[2]); }

現在它只建立了一個叫 variable 的變數,但沒有為其他值做變數。

還有很多集合型別,及許許多多使用陣列、向量和元組的方式。我們也將學習更多關於它們的知識,但我們將先學習控制流程。

控制流程

YouTube 上觀看本章內容: Part 1 及 Part 2

控制流程(control flow)的意思是告訴你的程式碼在不同的情況下該怎麼做。最簡單的控制流程是 if。

fn main() { let my_number = 5; if my_number == 7 { println!("It's seven"); } }

另外注意,你用的是 == 而不是 =。== 是用來比較的,= 是用來賦值的(給一個值)。另外注意,我們寫的是 if my_number == 7 而不是 if (my_number == 7)。在 Rust 中,你不需要在 if 條件用括號。

else if 和 else 給你更多的控制:

fn main() { let my_number = 5; if my_number == 7 { println!("It's seven"); } else if my_number == 6 { println!("It's six") } else { println!("It's a different number") } }

印出 It's a different number,因為它不等於 7 或 6。

您可以使用 &&(和)和 ||(或)來新增更多條件。

fn main() { let my_number = 5; if my_number % 2 == 1 && my_number > 0 { // % 2 表示除以2之後的餘下的數 println!("It's a positive odd number"); } else if my_number == 6 { println!("It's six") } else { println!("It's a different number") } }

印出 It's a positive odd number,因為當你把它除以 2 時,你有餘數 1,且它大於0。

你可以看到,過多的 if、else 和 else if 會很難讀。在這種情況下,你可以使用 match 來代替,它看起來更乾淨。但是您必須為每一個可能的結果進行匹配(match)。例如,這將無法運作:

fn main() { let my_number: u8 = 5; match my_number { 0 => println!("it's zero"), 1 => println!("it's one"), 2 => println!("it's two"), // ⚠️ } }

編譯器說:

error[E0004]: non-exhaustive patterns: `3u8..=std::u8::MAX` not covered

--> src\main.rs:3:11

|

3 | match my_number {

| ^^^^^^^^^ pattern `3u8..=std::u8::MAX` not covered

這就意味著"你告訴我 0 到 2,但 u8 可以到 255。那 3 呢?4 呢?5 呢?"以此類推。所以你可以加上 _,意思是"其他任何東西"。

fn main() { let my_number: u8 = 5; match my_number { 0 => println!("it's zero"), 1 => println!("it's one"), 2 => println!("it's two"), _ => println!("It's some other number"), } }

印出 It's some other number。

記住這些匹配的規則:

- 你寫下

match,然後做一個{}程式碼區塊。 - 在左邊寫上模式,用

=>胖箭頭說明匹配時該怎麼做。 - 每一行稱為一個"分支(arm)"。

- 在分支之間放一個逗號(不是分號)。

你可以用匹配結果來宣告一個值:

fn main() { let my_number = 5; let second_number = match my_number { 0 => 0, 5 => 10, _ => 2, }; }

second_number 將是 10。你看到最後的分號了嗎?那是因為,在 match 結束後,我們實際上告訴了編譯器這個資訊:let second_number = 10;

你也可以在更復雜的事情上進行匹配。你要用元組來做到。

fn main() { let sky = "cloudy"; let temperature = "warm"; match (sky, temperature) { ("cloudy", "cold") => println!("It's dark and unpleasant today"), ("clear", "warm") => println!("It's a nice day"), ("cloudy", "warm") => println!("It's dark but not bad"), _ => println!("Not sure what the weather is."), } }

印出 It's dark but not bad,因為它與 sky 和 temperature 的 "cloudy" 和 "warm" 相匹配。

你甚至可以把 if 放在 match 裡面。這稱為 "match guard":

fn main() { let children = 5; let married = true; match (children, married) { (children, married) if married == false => println!("Not married with {} children", children), (children, married) if children == 0 && married == true => println!("Married but no children"), _ => println!("Married? {}. Number of children: {}.", married, children), } }

這將印出 Married? true. Number of children: 5.

在匹配時,你可以隨意多次使用 _。在這個關於顏色的匹配中,我們有三個顏色,但一次只能選中一個。

fn match_colours(rbg: (i32, i32, i32)) { match rbg { (r, _, _) if r < 10 => println!("Not much red"), (_, b, _) if b < 10 => println!("Not much blue"), (_, _, g) if g < 10 => println!("Not much green"), _ => println!("Each colour has at least 10"), } } fn main() { let first = (200, 0, 0); let second = (50, 50, 50); let third = (200, 50, 0); match_colours(first); match_colours(second); match_colours(third); }

印出:

Not much blue

Each colour has at least 10

Not much green

這也說明了 match 陳述式的作用,因為在第一個例子中,它只印了 Not much blue。但是 first 也沒有多少綠色。match 陳述式總是在找到一個匹配項時停止,而不檢查其他的。這就是程式碼編譯得很好,但不是你想要的程式碼的一個好例子。

你可以做一個非常大的 match 陳述式來解決這個問題,但是使用 for 迴圈(loop)可能更好。我們將很快會討論到迴圈。

匹配必須回傳相同的型別。所以你不能這樣做:

fn main() { let my_number = 10; let some_variable = match my_number { 10 => 8, _ => "Not ten", // ⚠️ }; }

編譯器告訴你:

error[E0308]: `match` arms have incompatible types

--> src\main.rs:17:14

|

15 | let some_variable = match my_number {

| _________________________-

16 | | 10 => 8,

| | - this is found to be of type `{integer}`

17 | | _ => "Not ten",

| | ^^^^^^^^^ expected integer, found `&str`

18 | | };

| |_____- `match` arms have incompatible types

這樣也不行,原因同上。

fn main() { let some_variable = if my_number == 10 { 8 } else { "something else "}; // ⚠️ }

但是這樣就可以了,因為不是 match,所以你每次都有不同的 let 陳述式:

fn main() { let my_number = 10; if my_number == 10 { let some_variable = 8; } else { let some_variable = "Something else"; } }

你也可以使用 @ 給 match 表示式的值命名,然後你就可以使用它。在這個範例中,我們在函式中匹配 i32 輸入。如果是 4 或 13,我們要在 println! 陳述式中使用這個數字。否則,我們不需要使用它。

fn match_number(input: i32) { match input { number @ 4 => println!("{} is an unlucky number in China (sounds close to 死)!", number), number @ 13 => println!("{} is unlucky in North America, lucky in Italy! In bocca al lupo!", number), _ => println!("Looks like a normal number"), } } fn main() { match_number(50); match_number(13); match_number(4); }

印出:

Looks like a normal number

13 is unlucky in North America, lucky in Italy! In bocca al lupo!

4 is an unlucky number in China (sounds close to 死)!

結構體

YouTube 上觀看本章內容: Part 1 及 Part 2

有了結構體(struct),你可以建立自己的型別。在 Rust 中,你會無時無刻用著結構體,因為它們非常方便。結構體是用關鍵字 struct 建立的。結構體的名稱應該用大駝峰式命名法(UpperCamelCase,每個字首用大寫字母,不含空格)。如果你用全小寫的結構體,編譯器會告訴你。

結構體有三種類型。一種是"單元結構體"。單元的意思是"沒有任何東西"。對於一個單元結構體,你只需要寫名字和一個分號。

struct FileDirectory; fn main() {}

下一種是元組結構體(tuple struct),或者說是未具名結構體。之所以是"未具名",是因為你只需要寫型別,而不是欄位(field)名。元組結構體適合在你需要一個簡單的結構,並且不需要記住名字時。

struct Colour(u8, u8, u8); fn main() { let my_colour = Colour(50, 0, 50); // 從RGB (red, green, blue)做出顏色 println!("The second part of the colour is: {}", my_colour.1); }

印出 The second part of the colour is: 0。

第三種類型是具名結構體。這可能是最常見的結構體。在這個結構體中,你在 {} 程式碼區塊中宣告欄位名和型別。請注意,在具名結構體後面不要寫分號,因為它後面是一整個程式碼區塊。

struct Colour(u8, u8, u8); // 宣告一樣的 Colour 元組結構體 struct SizeAndColour { size: u32, colour: Colour, // 並且我們把它放在我們的新具名結構體裡 } fn main() { let my_colour = Colour(50, 0, 50); let size_and_colour = SizeAndColour { size: 150, colour: my_colour }; }

在具名結構體中,你也可以用逗號來分隔欄位。對於最後一個欄位,你可以加或不加逗號──這取決於你。SizeAndColour 在 colour 後面有一個逗號:

struct Colour(u8, u8, u8); // 宣告一樣的 Colour 結構體 struct SizeAndColour { size: u32, colour: Colour, // 並且我們把它放在我們的新具名結構體裡 } fn main() {}

但你不需要它。但總是放一個逗號可能是個好主意,因為有時你會改變欄位的順序:

struct Colour(u8, u8, u8); // 宣告一樣的 Colour 結構體 struct SizeAndColour { size: u32, colour: Colour // 這裡沒有逗號 } fn main() {}

然後我們決定改變順序...

struct SizeAndColour { colour: Colour // ⚠️ Whoops! 現在這裡沒有逗號。 size: u32, } fn main() {}

但無論哪種方式都不是很重要,所以你可以選擇是否要使用逗號。

我們建立一個 Country 結構體來舉例說明。Country 結構有 population、capital 和 leader_name 三個欄位。

struct Country { population: u32, capital: String, leader_name: String } fn main() { let population = 500_000; let capital = String::from("Elista"); let leader_name = String::from("Batu Khasikov"); let kalmykia = Country { population: population, capital: capital, leader_name: leader_name, }; }

你有沒有注意到,我們把同樣的東西寫了兩次?我們寫了 population: population、capital: capital 和 leader_name: leader_name。實際上,你不需要這樣做。如果欄位名和變數名相同,你就不用寫兩次。

struct Country { population: u32, capital: String, leader_name: String } fn main() { let population = 500_000; let capital = String::from("Elista"); let leader_name = String::from("Batu Khasikov"); let kalmykia = Country { population, capital, leader_name, }; }

列舉

YouTube 上觀看本章內容: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 及 Part 4

enum 是列舉(enumeration)的簡稱。它們看起來與結構體非常相似,但又有所不同。區別有:

- 當你想要一個東西和另一個東西時,使用

struct。 - 當你想要一個東西或另一個東西時,請使用

enum。

所以,結構體是用於多個事物在一起,而列舉則是用於多個選擇在一起。

要宣告列舉時,寫下 enum,並用程式碼區塊將包含的選項用逗號分隔。就像 struct 一樣,最後一部分的逗號則可有可無。我們將建立一個名為 ThingsInTheSky 的列舉:

enum ThingsInTheSky { Sun, Stars, } fn main() {}

這是個列舉,因為你可以看到太陽或星星:你必須選擇一個。這些叫做變體(variants)。

// 建立兩個選擇的列舉 enum ThingsInTheSky { Sun, Stars, } // 有這個函式我們可以用i32來建立ThingsInTheSky。 fn create_skystate(time: i32) -> ThingsInTheSky { match time { 6..=18 => ThingsInTheSky::Sun, // 介於6到18小時之間我們可以見到太陽 _ => ThingsInTheSky::Stars, // 除此之外,我們可以見到星星 } } // 有這個函式我們可以匹配到ThingsInTheSky的兩個選擇。 fn check_skystate(state: &ThingsInTheSky) { match state { ThingsInTheSky::Sun => println!("I can see the sun!"), ThingsInTheSky::Stars => println!("I can see the stars!") } } fn main() { let time = 8; // 這是 8 點鐘 let skystate = create_skystate(time); // create_skystate回傳ThingsInTheSky check_skystate(&skystate); // 給它參考那麼它就能讀到變數skystate }

印出 I can see the sun!。

你也可以將資料新增到列舉中。

enum ThingsInTheSky { Sun(String), // 現在每個變體都有字串 Stars(String), } fn create_skystate(time: i32) -> ThingsInTheSky { match time { 6..=18 => ThingsInTheSky::Sun(String::from("I can see the sun!")), // 這裡寫下字串 _ => ThingsInTheSky::Stars(String::from("I can see the stars!")), } } fn check_skystate(state: &ThingsInTheSky) { match state { ThingsInTheSky::Sun(description) => println!("{}", description), // 給字串命名為description那麼我們就能使用它 ThingsInTheSky::Stars(n) => println!("{}", n), // 或你能命名成 n。或其它任何東西──它無關緊要 } } fn main() { let time = 8; // 這是 8 點鐘 let skystate = create_skystate(time); // create_skystate 回傳 ThingsInTheSky check_skystate(&skystate); // 給它參考那麼它就能讀到變數skystate }

印出來的結果一樣:I can see the sun!。

你也可以"匯入(import)"一個列舉,這樣你就不用打那麼多字了。下面這個例子裡,我們每次在匹配我們的 mood 時都要輸入 Mood:::

enum Mood { Happy, Sleepy, NotBad, Angry, } fn match_mood(mood: &Mood) -> i32 { let happiness_level = match mood { Mood::Happy => 10, // 我們每次都要輸入 Mood:: Mood::Sleepy => 6, Mood::NotBad => 7, Mood::Angry => 2, }; happiness_level } fn main() { let my_mood = Mood::NotBad; let happiness_level = match_mood(&my_mood); println!("Out of 1 to 10, my happiness is {}", happiness_level); }

印出的是 Out of 1 to 10, my happiness is 7。讓我們匯入,這樣我們就可以少打點字了。要匯入所有的東西時寫做 *。注意:它和反參考關鍵字的 * 一樣,但完全不同。

enum Mood { Happy, Sleepy, NotBad, Angry, } fn match_mood(mood: &Mood) -> i32 { use Mood::*; // 我們匯入Mood裡的所有東西。現在我們可以只寫Happy、Sleepy等變體名。 let happiness_level = match mood { Happy => 10, // 我們不用再寫 Mood:: 了 Sleepy => 6, NotBad => 7, Angry => 2, }; happiness_level } fn main() { let my_mood = Mood::Happy; let happiness_level = match_mood(&my_mood); println!("Out of 1 to 10, my happiness is {}", happiness_level); }

enum 的一部分也可以轉變成整數。這是因為 Rust 給 enum 提供了以 0 開頭的數字給每個分支各自使用。如果你的列舉中沒有任何其他資料的話,你可以拿它來做些事情。

enum Season { Spring, // 如果這是 Spring(String) 或其它東西,它就不能這樣用 Summer, Autumn, Winter, } fn main() { use Season::*; let four_seasons = vec![Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter]; for season in four_seasons { println!("{}", season as u32); } }

印出:

0

1

2

3

不過如果你想的話,你也可以給它一個不同的數字──Rust 並不在意,可以用同樣的方式來使用它。只要在你想要有數值的變體加上 = 和數字。你不必給數字到所有變體。但如果你不這樣做,Rust 就會給變體從前一個分支數字加 1 的數字。

enum Star { BrownDwarf = 10, RedDwarf = 50, YellowStar = 100, RedGiant = 1000, DeadStar, // 想想看這個數字會有多少? } fn main() { use Star::*; let starvec = vec![BrownDwarf, RedDwarf, YellowStar, RedGiant]; for star in starvec { match star as u32 { size if size <= 80 => println!("Not the biggest star."), // 記得: size 沒有任何意思。只不過是我們為了可以列印所選的名稱 size if size >= 80 => println!("This is a good-sized star."), _ => println!("That star is pretty big!"), } } println!("What about DeadStar? It's the number {}.", DeadStar as u32); }

印出:

Not the biggest star.

Not the biggest star.

This is a good-sized star.

This is a good-sized star.

What about DeadStar? It's the number 1001.

DeadStar 本來是 4 號,但現在是 1001。

使用多種型別的列舉

你知道向量、陣列等等之中的元素都需要相同的型別(只有 tuple 不同)。但其實你可以用列舉來放不同的型別。想象一下,我們想要有個向量,有 u32 或 i32。當然,你可以做出 Vec<(u32, i32)>(帶有 (u32, i32) 元組的向量),但是我們想要每次只有一種。所以這裡可以使用列舉。這是簡單的範例:

enum Number { U32(u32), I32(i32), } fn main() {}

所以這有兩個變體:U32 變體裡有 u32,I32 變體裡有 i32。U32 和 I32 只是我們取的名字。它們可以取名叫 UThirtyTwo、IThirtyTwo 或其他任何東西。

現在,如果我們把它們放到向量中,我們就會有 Vec<Number>,因為都是同一個型別編譯器會很開心。編譯器並不在乎我們有的是 u32 或者是 i32,因為它們都在一個叫做 Number 的單一型別裡面。因為它是列舉,你必須選擇一種,這就是我們想要的。我們將使用 .is_positive() 方法來挑選。如果是 true,那麼我們將選擇 U32,如果是 false,那麼我們將選擇 I32。

現在程式碼像這樣:

enum Number { U32(u32), I32(i32), } fn get_number(input: i32) -> Number { let number = match input.is_positive() { true => Number::U32(input as u32), // 如果是正數改成 u32 false => Number::I32(input), // 不然就給數字因為它已經是 i32 }; number } fn main() { let my_vec = vec![get_number(-800), get_number(8)]; for item in my_vec { match item { Number::U32(number) => println!("It's a u32 with the value {}", number), Number::I32(number) => println!("It's an i32 with the value {}", number), } } }

印出了我們想看到的結果:

It's an i32 with the value -800

It's a u32 with the value 8

迴圈

有了迴圈,你可以告訴 Rust 繼續做某件事,直到你想停止它。你也能使用 loop 來啟動一個不會停止的迴圈,除非你告訴它何時 break(中斷)。

fn main() { // 這個程式永不停止 loop { } }

那讓我們告訴編譯器什麼時候能停止。

fn main() { let mut counter = 0; // 設定計數器為 0 loop { counter +=1; // 計數器遞增 1 println!("The counter is now: {}", counter); if counter == 5 { // 當計數器 == 5 時停止 break; } } }

將會印出:

The counter is now: 1

The counter is now: 2

The counter is now: 3

The counter is now: 4

The counter is now: 5

如果你的迴圈裡面還有迴圈,你可以給它們命名。有了名字,你可以告訴 Rust 要從哪個迴圈中 break 出來。使用 ' (稱為 "tick") 和 : 來給它命名:

fn main() { let mut counter = 0; let mut counter2 = 0; println!("Now entering the first loop."); 'first_loop: loop { // 給第一個迴圈名字 counter += 1; println!("The counter is now: {}", counter); if counter > 9 { // 在迴圈裡開始第二個迴圈 println!("Now entering the second loop."); 'second_loop: loop { // 現在我們在 'second_loop 裡面 println!("The second counter is now: {}", counter2); counter2 += 1; if counter2 == 3 { break 'first_loop; // 中斷到 'first_loop 標籤外我們才能離開程式 } } } } }

將會印出:

Now entering the first loop.

The counter is now: 1

The counter is now: 2

The counter is now: 3

The counter is now: 4

The counter is now: 5

The counter is now: 6

The counter is now: 7

The counter is now: 8

The counter is now: 9

The counter is now: 10

Now entering the second loop.

The second counter is now: 0

The second counter is now: 1

The second counter is now: 2

while 迴圈是指在某件事物還在 true 時繼續運作的迴圈。每一次迴圈,Rust 都會檢查它是否仍然是 true。如果變成 false,Rust 會停止迴圈。

fn main() { let mut counter = 0; while counter < 5 { counter +=1; println!("The counter is now: {}", counter); } }

for 迴圈讓你告訴 Rust 每次要做什麼。但是在 for 迴圈中,迴圈會在一定次數後停止。for 迴圈經常使用範圍(range)。你能用 .. 和 ..= 來建立範圍。

..建立一個排除的範圍:0..3建立0, 1, 2。..=建立一個包含的範圍:0..=3建立0, 1, 2, 3。

fn main() { for number in 0..3 { println!("The number is: {}", number); } for number in 0..=3 { println!("The next number is: {}", number); } }

印出:

The number is: 0

The number is: 1

The number is: 2

The next number is: 0

The next number is: 1

The next number is: 2

The next number is: 3

同時注意到,number 成為 0..3 的變數名。我們也能叫它做 n,或者 ntod_het___hno_f,或者任何名字。然後我們就可以在 println! 中使用這個名字。

如果你不需要變數名,就用 _。

fn main() { for _ in 0..3 { println!("Printing the same thing three times"); } }

印出:

Printing the same thing three times

Printing the same thing three times

Printing the same thing three times

因為我們每次都沒有給它任何數字來列印。

而實際上,如果你給了變數名卻沒用,Rust 會告訴你:

fn main() { for number in 0..3 { println!("Printing the same thing three times"); } }

印出的內容和上面一樣。程式編譯正常,但 Rust 會提醒你沒有使用 number:

warning: unused variable: `number`

--> src\main.rs:2:9

|

2 | for number in 0..3 {

| ^^^^^^ help: if this is intentional, prefix it with an underscore: `_number`

Rust 建議寫 _number 而不是 _。在變數名前加上 _ 意味著 "也許我以後會用到它"。但是只用 _ 意味著"我根本不關心這個變數"。所以,如果你以後會使用它們,並且不想讓編譯器告訴你,你可以在變數名前面加上_。

你也可以用 break 來回傳值。只要把值寫在 break 後面以及 ;。這個有 loop 和 break 的範例賦值給 my_number。

fn main() { let mut counter = 5; let my_number = loop { counter +=1; if counter % 53 == 3 { break counter; } }; println!("{}", my_number); }

印出 56。break counter; 的意思是"中斷並回傳計數器的值"。而且因為整個區塊以 let 開始,my_number 最後會得到回傳值。

現在我們知道了如何使用迴圈,對於我們之前的顏色"匹配"問題這是更好的解決方案。這個解決方案更好是因為我們要比較所有的東西,而"for"迴圈會檢視每一項元素。

fn match_colours(rbg: (i32, i32, i32)) { println!("Comparing a colour with {} red, {} blue, and {} green:", rbg.0, rbg.1, rbg.2); let new_vec = vec![(rbg.0, "red"), (rbg.1, "blue"), (rbg.2, "green")]; // 將顏色放進向量。裡面是含顏色名的元組 let mut all_have_at_least_10 = true; // 從true開始。我們會設定為false如果其中一種顏色少於10 for item in new_vec { if item.0 < 10 { all_have_at_least_10 = false; // 現在是false println!("Not much {}.", item.1) // 接著我們印出顏色。 } } if all_have_at_least_10 { // 檢查是否仍是true,是就印出 println!("Each colour has at least 10.") } println!(); // 多加一行 } fn main() { let first = (200, 0, 0); let second = (50, 50, 50); let third = (200, 50, 0); match_colours(first); match_colours(second); match_colours(third); }

印出:

Comparing a colour with 200 red, 0 blue, and 0 green:

Not much blue.

Not much green.

Comparing a colour with 50 red, 50 blue, and 50 green:

Each colour has at least 10.

Comparing a colour with 200 red, 50 blue, and 0 green:

Not much green.

實作結構體和列舉

從這裡開始你可以給予你的結構體和列舉一些真正的威力。要對 struct 或 enum 呼叫的函式,要寫在 impl 區塊。這些函式被稱為方法(method)。impl 區塊中的方法有兩類。

- 方法:這些方法會取用 self(或是 &self 或 &mut self)。正規方法使用"."(英文句號)。

.clone()是一個正規方法的例子。 - 關聯函式(associated function, 在某些語言中被稱為"靜態(static)"方法):這些函式不使用 self。關聯的意思是"有相關的"。它們的書寫方式不同,用的是

::。String::from()是一個關聯函式,Vec::new()也是。你看到的關聯函式最常被用來建立新變數。

我們將在我們的範例中建立 Animal 並印出它們。

對於新的 struct 或 enum,如果你想使用 {:?} 印出來,你需要給它Debug,我們也將會這樣做。如果你在結構體或列舉上面寫了 #[derive(Debug)],那麼你就可以用 {:?} 印出來。這些帶有 #[] 的訊息被稱為屬性(attributes)。你有時可以用它們來告訴編譯器給你的結構體像是 Debug 的能力。屬性有很多種,我們以後會學到。但是 derive 可能是最常見的,你經常在結構體和列舉上面看到它。

#[derive(Debug)] struct Animal { age: u8, animal_type: AnimalType, } #[derive(Debug)] enum AnimalType { Cat, Dog, } impl Animal { fn new() -> Self { // Self 指的是 Animal。 // 你也可以寫 Animal 而非 Self Self { // 當我們寫 Animal::new() 我們永遠會得到10歲的貓 age: 10, animal_type: AnimalType::Cat, } } fn change_to_dog(&mut self) { // 因為我們在Animal裡, &mut self 指的是 &mut Animal // 用 .change_to_dog() 把貓改成狗 // 有了 &mut self 我們就能更改 println!("Changing animal to dog!"); self.animal_type = AnimalType::Dog; } fn change_to_cat(&mut self) { // 用 .change_to_cat() 把狗改成貓 // 有了 &mut self 我們就能更改 println!("Changing animal to cat!"); self.animal_type = AnimalType::Cat; } fn check_type(&self) { // we want to read self match self.animal_type { AnimalType::Dog => println!("The animal is a dog"), AnimalType::Cat => println!("The animal is a cat"), } } } fn main() { let mut new_animal = Animal::new(); // 用關聯函式建立新動物 // 它是一隻10歲的貓 new_animal.check_type(); new_animal.change_to_dog(); new_animal.check_type(); new_animal.change_to_cat(); new_animal.check_type(); }

印出:

The animal is a cat

Changing animal to dog!

The animal is a dog

Changing animal to cat!

The animal is a cat

記住,Self(型別 Self)和 self(變數 self)是縮寫。(縮寫 = 簡寫方式)

所以在我們的程式碼中,Self = Animal。另外,fn change_to_dog(&mut self) 的意思是 fn change_to_dog(&mut Animal)。

下面再舉一個小例子。這次我們將在 enum 上使用 impl:

enum Mood { Good, Bad, Sleepy, } impl Mood { fn check(&self) { match self { Mood::Good => println!("Feeling good!"), Mood::Bad => println!("Eh, not feeling so good"), Mood::Sleepy => println!("Need sleep NOW"), } } } fn main() { let my_mood = Mood::Sleepy; my_mood.check(); }

印出 Need sleep NOW。

解構

我們再來多看些解構(destructuring)。你可以反過來透過使用 let 從結構體或列舉中獲取值。我們瞭解到這是 destructuring,因為你得到的變數不是結構體的一部分。現在你分別得到了它們的值。首先是一個簡單的範例:

struct Person { // 為個人資料做一個簡單的結構體 name: String, real_name: String, height: u8, happiness: bool } fn main() { let papa_doc = Person { // 建立變數 papa_doc name: "Papa Doc".to_string(), real_name: "Clarence".to_string(), height: 170, happiness: false }; let Person { // 解構 papa_doc name: a, real_name: b, height: c, happiness: d } = papa_doc; println!("They call him {} but his real name is {}. He is {} cm tall and is he happy? {}", a, b, c, d); }

印出:They call him Papa Doc but his real name is Clarence. He is 170 cm tall and is he happy? false

你可以看到它是反過來的。首先我們說 let papa_doc = Person { fields } 來建立結構體。然後我們說 let Person { fields } = papa_doc 來解構它。

你不必寫 name: a──你可以直接寫 name。但這裡我們寫 name: a 是因為我們想使用一個名字為 a 的變數。

現在再舉一個更大的例子。在這個例子中,我們有一個 City 結構體。我們給它一個 new 函式來做出它。然後我們有一個 process_city_values 函式來處理這些值。在函式中,我們只是建立了一個 Vec,但你可以想象,我們可以在解構它之後做更多的事情。

struct City { name: String, name_before: String, population: u32, date_founded: u32, } impl City { fn new(name: String, name_before: String, population: u32, date_founded: u32) -> Self { Self { name, name_before, population, date_founded, } } } fn process_city_values(city: &City) { let City { name, name_before, population, date_founded, } = city; // 現在我們有可分別使用的值了 let two_names = vec![name, name_before]; println!("The city's two names are {:?}", two_names); } fn main() { let tallinn = City::new("Tallinn".to_string(), "Reval".to_string(), 426_538, 1219); process_city_values(&tallinn); }

印出 The city's two names are ["Tallinn", "Reval"]。

參考和點運算子

我們學過當你有一個參考時,你要用 * 來取得值。參考是一種不同的型別,所以這是無法執行的:

fn main() { let my_number = 9; let reference = &my_number; println!("{}", my_number == reference); // ⚠️ }

編譯器印出:

error[E0277]: can't compare `{integer}` with `&{integer}`

--> src\main.rs:5:30

|

5 | println!("{}", my_number == reference);

| ^^ no implementation for `{integer} == &{integer}`

所以我們把第 5 行改成 println!("{}", my_number == *reference);,現在印出的是 true,因為現在是比較 i32 == i32,而不是比較 i32 == &i32。這就是所謂的反參考。

但是當你使用方法時,Rust 會為你反參考。方法中的 . 被稱為點運算子(dot operator),用來免費做反參考。

首先,讓我們寫一個有 u8 欄位的結構。然後,我們將對它做參考,並嘗試進行比較。它將無法執行:

struct Item { number: u8, } fn main() { let item = Item { number: 8, }; let reference_number = &item.number; // 型別是 &u8 println!("{}", reference_number == 8); // ⚠️ &u8 和 u8 不能比較 }

為了讓它能執行,我們需要去反參考:println!("{}", *reference_number == 8);。

但用了點運算子,我們就不需要*。例如:

struct Item { number: u8, } fn main() { let item = Item { number: 8, }; let reference_item = &item; println!("{}", reference_item.number == 8); // 我們不要需寫成 *reference_item.number }

現在讓我們為 Item 建立方法來比較 number 與另一個數字。我們不需要在任何地方使用 *:

struct Item { number: u8, } impl Item { fn compare_number(&self, other_number: u8) { // 接受 self 的參考 println!("Are {} and {} equal? {}", self.number, other_number, self.number == other_number); // 我們不需要寫 *self.number } } fn main() { let item = Item { number: 8, }; let reference_item = &item; // 型別 &Item let reference_item_two = &reference_item; // 型別 &&Item item.compare_number(8); // 方法可以執行 reference_item.compare_number(8); // 它在這裡也可以執行 reference_item_two.compare_number(8); // 還有這裡 }

所以只要記住:當你使用 . 運算子時,你不需要擔心有沒有 *。

泛型

在函式中,你要寫出拿什麼型別作為輸入:

fn return_number(number: i32) -> i32 { println!("Here is your number."); number } fn main() { let number = return_number(5); }

但是如果你想用的不僅僅是 i32 呢?你可以用泛型(Generics)來解決。泛型的意思是 "也許是某一種型別,也許是另一種型別"。

泛型的寫法要用角括號裡面加上型別,像這樣:<T> 這個意思是"你放進函式的任意型別"。通常泛型會使用一個大寫字母的型別(T、U、V等),儘管你不必只使用一個字母。

這個範例是你如何改變函式讓它用泛型:

fn return_number<T>(number: T) -> T { println!("Here is your number."); number } fn main() { let number = return_number(5); }

重點是函式名稱後的 <T>。如果沒有這個,Rust 會認為 T 是一個具體的(concrete,具體的 = 不是泛型的)型別,像是 String 或 i8。

如果我們能寫出型別名,就更容易理解了。看看我們把 T 改成 MyType 會發生什麼:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn return_number(number: MyType) -> MyType { // ⚠️ println!("Here is your number."); number } }

大家可以看到,MyType 是具體的,不是泛型的。所以我們需要寫成這樣,它現在就可以執行了:

fn return_number<MyType>(number: MyType) -> MyType { println!("Here is your number."); number } fn main() { let number = return_number(5); }

所以單字母 T 是給人眼看的,但函式名稱後的部分是給編譯器的"眼睛"看的。沒有了它,就不是泛型了。

現在我們再回到型別 T,因為 Rust 程式碼通常使用 T。

你會記得 Rust 中有些型別是 Copy,有些是 Clone,有些是 Display,有些是 Debug,等等。有 Debug,我們可以用 {:?} 來列印。所以現在大家可以看到,我們如果要印出 T 就有問題了:

fn print_number<T>(number: T) { println!("Here is your number: {:?}", number); // ⚠️ } fn main() { print_number(5); }

print_number 需要 Debug 印出 number,但是 T 是一個有 Debug 的型別嗎?也許不是。也許它沒有 #[derive(Debug)],誰知道呢?編譯器也不知道,所以它給了錯誤:

error[E0277]: `T` doesn't implement `std::fmt::Debug`

--> src\main.rs:29:43

|

29 | println!("Here is your number: {:?}", number);

| ^^^^^^ `T` cannot be formatted using `{:?}` because it doesn't implement `std::fmt::Debug`

T 沒有實作 Debug。那麼我們是否要為 T 實現 Debug 呢?不,因為我們不知道(具體的) T 是什麼。但是我們可以告訴函式:"別擔心,因為這個函式用的任何 T 型別都會有 Debug"

use std::fmt::Debug; // 聲明 Debug 是來自 std::fmt::Debug。所以後面我們可以只寫 'Debug'。 fn print_number<T: Debug>(number: T) { // <T: Debug> 是重點 println!("Here is your number: {:?}", number); } fn main() { print_number(5); }

所以現在編譯器知道:"好的,這個型別 T 會有 Debug"。現在程式碼執行了,因為 i32 有 Debug。現在我們可以給它很多型別。String、&str 等,因為它們都有 Debug.

現在我們可以建立結構,並用 #[derive(Debug)] 給它實作 Debug,所以現在我們也可以印出它。我們的函式能接受 i32、Animal 結構體及更多型別:

use std::fmt::Debug; #[derive(Debug)] struct Animal { name: String, age: u8, } fn print_item<T: Debug>(item: T) { println!("Here is your item: {:?}", item); } fn main() { let charlie = Animal { name: "Charlie".to_string(), age: 1, }; let number = 55; print_item(charlie); print_item(number); }

印出:

Here is your item: Animal { name: "Charlie", age: 1 }

Here is your item: 55

有時我們在泛型函式中需要不止一種型別。我們必須寫出每個型別的名稱,並思考我們想要如何使用它。在這個範例中,我們想要兩個型別。首先我們想印出型別為 T 的陳述式。用 {} 列印更好,所以我們會要求用 Display 來列印 T。

下個是型別 U 和 num_1 和 num_2 這兩個型別為 U(U 是某種數字)的變數。我們想要比較它們,所以我們需要 PartialOrd。這個特性讓我們可以使用 <、>、== 等。我們也想印出它們,所以我們也要求有 Display 來印出 U。

use std::fmt::Display; use std::cmp::PartialOrd; fn compare_and_display<T: Display, U: Display + PartialOrd>(statement: T, num_1: U, num_2: U) { println!("{}! Is {} greater than {}? {}", statement, num_1, num_2, num_1 > num_2); } fn main() { compare_and_display("Listen up!", 9, 8); }

印出 Listen up!! Is 9 greater than 8? true。

所以 fn compare_and_display<T: Display, U: Display + PartialOrd>(statement: T, num_1: U, num_2: U) 說得是:

- 函式名稱是

compare_and_display, - 第一個型別是泛型的 T。它必須是一個可以用 {} 列印的型別。

- 下一個型別是泛型的 U。它必須是一個可以用 {} 列印的型別。另外,它必須是一個可以比較的型別(使用

>、<和==)。

現在我們可以給 compare_and_display 不同的型別。statement 可以是 String、&str,或任何有 Display 的型別。

為了讓泛型函式更容易讀懂,我們也可以這樣寫得像這個範例,在程式碼區塊之前用 where。

use std::cmp::PartialOrd; use std::fmt::Display; fn compare_and_display<T, U>(statement: T, num_1: U, num_2: U) where T: Display, U: Display + PartialOrd, { println!("{}! Is {} greater than {}? {}", statement, num_1, num_2, num_1 > num_2); } fn main() { compare_and_display("Listen up!", 9, 8); }

尤其當你有很多泛型型別時,使用 where 是一個好主意。

還要注意:

- 如果你有一個型別 T 和另一個型別 T,它們必須是相同的。

- 如果你有一個型別 T 和另一個型別 U,它們可以是不同的。但它們也可以是相同的。

比如說:

use std::fmt::Display; fn say_two<T: Display, U: Display>(statement_1: T, statement_2: U) { // T型別要有 Display,U型別要有 Display println!("I have two things to say: {} and {}", statement_1, statement_2); } fn main() { say_two("Hello there!", String::from("I hate sand.")); // T型別是 &str,但U型別是 String。 say_two(String::from("Where is Padme?"), String::from("Is she all right?")); // 兩者型別皆是 String。 }

印出:

I have two things to say: Hello there! and I hate sand.

I have two things to say: Where is Padme? and Is she all right?

Option 和 Result

我們現在理解了列舉和泛型,所以我們也能理解 Option 和 Result。Rust 用這兩種列舉來使程式碼更安全。

我們將從 Option 開始。

Option

當你有一個值,它可能存在,也可能不存在時,你就該用 Option。當一個值存在時它就是 Some(value),不存在時就是 None,下面是一個可以用Option 來改進的壞程式碼範例。

// ⚠️ fn take_fifth(value: Vec<i32>) -> i32 { value[4] } fn main() { let new_vec = vec![1, 2]; let index = take_fifth(new_vec); }

當我們執行這段程式碼時,它發生恐慌(panic)。這是訊息:

thread 'main' panicked at 'index out of bounds: the len is 2 but the index is 4', src\main.rs:34:5

恐慌的意思是,程式在問題發生前就停止了。Rust 看到函式想要做些不可能的事情,就會停止。它"解開(unwind)堆疊"(從堆疊中取出值),並告訴你"對不起,我不能那樣做"。

所以現在我們將回傳型別從 i32 改為 Option<i32>。這意味著"如果有的話給我 Some(i32),如果沒有的話給我 None"。我們說 i32 是"包"在 Option 裡面,也就是說它放在 Option 裡面。你必須做些事情才能把這個值取出來。

fn take_fifth(value: Vec<i32>) -> Option<i32> { if value.len() < 5 { // .len() 給出向量的長度。 // 它必需是至少是 5。 None } else { Some(value[4]) } } fn main() { let new_vec = vec![1, 2]; let bigger_vec = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; println!("{:?}, {:?}", take_fifth(new_vec), take_fifth(bigger_vec)); }

印出的是 None, Some(5)。這下好了,因為現在我們再也不恐慌了。但是我們要如何得到 5 這個值呢?

我們可以用 .unwrap() 從 Option 裡面得取值,但要小心使用 .unwrap()。這就像拆禮物一樣:也許裡面有好東西,也許裡面有條憤怒的蛇。只有在你確定的情況下,你才會想要用 .unwrap()。如果你拆開一個 None 的值,程式就會恐慌。

// ⚠️ fn take_fifth(value: Vec<i32>) -> Option<i32> { if value.len() < 5 { None } else { Some(value[4]) } } fn main() { let new_vec = vec![1, 2]; let bigger_vec = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; println!("{:?}, {:?}", take_fifth(new_vec).unwrap(), // 這個是 None。 .unwrap() 會恐慌! take_fifth(bigger_vec).unwrap() ); }

訊息是:

thread 'main' panicked at 'called `Option::unwrap()` on a `None` value', src\main.rs:14:9

但我們可以不需要用 .unwrap()。我們能用 match。那麼我們就可以把我們有 Some 的值印出來,如果是 None 的值就不要碰。比如說:

fn take_fifth(value: Vec<i32>) -> Option<i32> { if value.len() < 5 { None } else { Some(value[4]) } } fn handle_option(my_option: Vec<Option<i32>>) { for item in my_option { match item { Some(number) => println!("Found a {}!", number), None => println!("Found a None!"), } } } fn main() { let new_vec = vec![1, 2]; let bigger_vec = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; let mut option_vec = Vec::new(); // 用新的向量存放我們的 option // 向量的型別: Vec<Option<i32>>。那是 Option<i32> 的向量。 option_vec.push(take_fifth(new_vec)); // 這會推送 "None" 進向量 option_vec.push(take_fifth(bigger_vec)); // 這會推送 "Some(5)" 進向量 handle_option(option_vec); // handle_option 查看向量裡的每個 option。 // 並印出值如果是 Some。如果是 None 就不碰。 }

印出:

Found a None!

Found a 5!

因為我們知道泛型,所以我們能夠讀懂 Option 的程式碼。它看起來像這樣:

enum Option<T> { None, Some(T), } fn main() {}

要記得的重點是:有了 Some,你就有了型別為 T 的值(任何型別)。還要注意的是,enum 名字後面有圍繞著 T 的角括號是用來告訴編譯器它是泛型。且它沒有 Display 這樣的特徵(trait)或任何東西來限制它,所以它可以是任何東西。但 None 的話,你就什麼都沒有。

所以在 Option 的 match 陳述式中,你不能說:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // 🚧 Some(value) => println!("The value is {}", value), None(value) => println!("The value is {}", value), }

因為 None 就只是 None。

當然,還有更簡單的方式來使用 Option。在這段程式碼中,我們將會使用一個叫做 .is_some() 的方法來告訴我們它是否是 Some。(對,還有個叫做 .is_none() 的方法。)在這個更簡單的方式中,我們不再需要 handle_option() 了。我們也不需要存放 Option 的向量了。

fn take_fifth(value: Vec<i32>) -> Option<i32> { if value.len() < 5 { None } else { Some(value[4]) } } fn main() { let new_vec = vec![1, 2]; let bigger_vec = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; let vec_of_vecs = vec![new_vec, bigger_vec]; for vec in vec_of_vecs { let inside_number = take_fifth(vec); if inside_number.is_some() { // 如果我們得到 Some,.is_some() 就回傳 true,None 就回傳 false println!("We got: {}", inside_number.unwrap()); // 因為我們已經檢查過了,現在它能安全的使用 .unwrap() } else { println!("We got nothing."); } } }

印出:

We got nothing.

We got: 5

Result

Result 和 Option 類似,但區別是:

- Option 和

Some或None有關 (有值或無值), - Result 和

Ok或Err有關 (成功的,或錯誤的結果)。

所以 Option 是用在如果你思考的是:"也許會有東西,也許不會有。"但 Result 則是用在如果你思考的是:"也許會失敗。"

比較一下,這是 Option 和 Result 的簽名(signature)。

enum Option<T> { None, Some(T), } enum Result<T, E> { Ok(T), Err(E), } fn main() {}

所以 Result 在 "Ok" 裡面有值,在 "Err" 裡面也有值。這是因為錯誤裡通常有包含描述錯誤的資訊。

Result<T, E> 的意思是你要想好 Ok 要回傳什麼,Err 要回傳什麼。其實,你可以決定任何事情。甚至這樣也可以:

fn check_error() -> Result<(), ()> { Ok(()) } fn main() { check_error(); }

check_error 說"如果得到 Ok 就回傳 (),如果得到 Err 就回傳 ()"。然後我們用 () 回傳 Ok。

編譯器給了我們有趣的警告:

warning: unused `std::result::Result` that must be used

--> src\main.rs:6:5

|

6 | check_error();

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

|

= note: `#[warn(unused_must_use)]` on by default

= note: this `Result` may be an `Err` variant, which should be handled

這是真的:我們只回傳了 Result,但它可能是 Err。所以讓我們稍微處理一下這個錯誤,儘管我們仍然沒有真的做任何事情。

fn give_result(input: i32) -> Result<(), ()> { if input % 2 == 0 { return Ok(()) } else { return Err(()) } } fn main() { if give_result(5).is_ok() { println!("It's okay, guys") } else { println!("It's an error, guys") } }

印出 It's an error, guys。所以我們只處理了第一個錯誤。

記住,輕鬆檢查的四種方法是.is_some()、is_none()、is_ok() 和 is_err()。

有時一個帶有 Result 的函式會用 String 來表示 Err 的值。這不是最好的方法,但比我們目前所做的要好一些。

fn check_if_five(number: i32) -> Result<i32, String> { match number { 5 => Ok(number), _ => Err("Sorry, the number wasn't five.".to_string()), // 這是我們的錯誤訊息 } } fn main() { let mut result_vec = Vec::new(); // 建立新的向量放結果 for number in 2..7 { result_vec.push(check_if_five(number)); // 推送每個結果進向量 } println!("{:?}", result_vec); }

我們的向量印出: